Arabian Opera Nights

January 2008 in Articles

Architecture and opera came together at the end-and in the aftermath-of Frank Lloyd Wright\’s career, but not in the manner that America\’s most famous architect might have envisaged. His final masterpiece, the spiralling, seashell-inspired Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, stands on New York\’s Upper East Side, a short flit across Central Park from where the Metropolitan Opera would move in 1966, seven years after the architect\’s death-another landmark building, but very different from the sort of opera house that occupied Wright during his final years. And though few architects actually make it into an opera, that happened in 1993 when Daron Hagen\’s Shining Brow (premiered by Madison Opera and since revived in several places) revisited the personal turmoil of an earlier phase in Wright\’s life-his estrangement from the first of his three wives, his relationship with Mamah Cheney and the notorious circumstances of her death in an arsonist\’s fire at Taliesin.

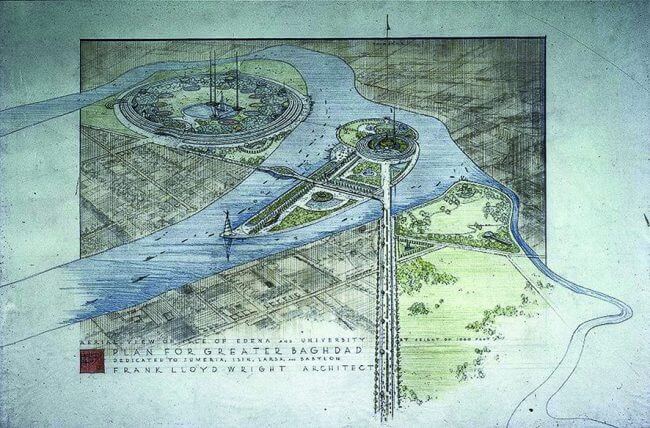

Wright\’s only New York building was completed shortly after his death in 1959, the culmination of a 16-year project, but during 1957 and \’58 he was more concerned with something that might have become his magnum opus: beginning with a commission for an opera house in Baghdad, he developed a far-reaching ‘Plan for Greater Baghdad\’, a scheme largely forgotten now but perhaps of extra interest today in the light of recent events. Compared with Wright\’s quintessential ‘Prairie style\’-extended low buildings, gently sloping roofs, suppressed chimneys, natural materials-familiar from many of his 350-plus houses, the Baghdad plans were exotic and on a huge scale. Yet their positively holistic level of integration was nothing new for Wright, who from the time he began working so intensively in Chicago\’s Oak Park suburb in the early 1900s had been interested in community planning. Another more specific precedent was the Imperial Hotel ensemble he completed in Tokyo in 1922.

In stark and tragic contrast to today\’s Republican-New Labour Baghdad project, it is sobering to recall how many great western architects worked during the 1950s in what was then still a new country (King Faisal I having been installed by the British only in 1921). Apart from Wright, the list included Gio Ponti, Alvar Aalto (his art museum was never realized), Walter Gropius (Baghdad University) and Le Corbusier (whose sports hall eventually became the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium). Wright arrived in Baghdad for a visit in May 1957, just one month short of his 90th birthday, and was feted. After two audiences with King Faisal II, he left with permission not only to build the originally proposed opera house but to incorporate it into development of a vast site in the middle of the Tigris River. Previously known as Pig Island, the uninhabited area was, Wright believed, the site of the Garden of Eden, and he renamed it Isle of Edena. By July 1957, in a speech back in the United States, he said: ‘I happen to be doing a cultural centre for a place where civilization was invented-that is, Iraq. Before Iraq was destroyed it was a beautiful circular city built by Harun al-Rashid, but the Mongols came from the north and practically destroyed it. Now what is left of the city has struck oil and they have immense sums of money. They can bring back the city of Harun al-Rashid today. They are not likely to do it because a lot of western architects are in there already building skyscrapers all over the place, and they are going to meet the destruction that is barging in on all big western cities. So it seems to me vital over there to try and make them see how foolish it is to join that western procession.\’

By harking back to the great centre of civilization founded in 762 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur, a fabled city built on a perfect circle and a place of learning that reached its apex of fame under al-Rashid\’s reign (Wright\’s speech, quoted above, overlooked al-Mansur\’s role in establishing Baghdad), the 20th-century architect was recalling the world of the Arabian Nights tales. Especially popular during his youth, these tales (many featuring al-Rashid himself) were fondly remembered by Wright, to the extent that he even decorated his children\’s playhouse with a mural showing ‘The Fisherman and the Genie\’. Yet Wright\’s attraction to the world of al-Rashid and the Arabian Nights was not a simplistic western fantasy, as detractors of the project have suggested, nor was it an example of the Orientalism soon to be decried by Edward Said. It delved deeply into Baghdad\’s heritage. By making his cultural complex ‘worthy of a king\’, however, Wright was bound to run into trouble. Following the military coup of July 1958, and the assassination of both Faisal II and Crown Prince Abdul Ilah, the project was rejected. Not only was it too extravagant for the military leadership, it was too closely and personally identified with the old monarchy. Nor was an opera house considered relevant.

What would it have looked like? Plans survive, but many got lost during the 1958 coup. Nezam Amery, a young Persian apprentice of Wright\’s who had recently returned to Tehran and established his own practice, acted as the great architect\’s Middle Eastern representative and was in Baghdad when the revolution broke out. Narrowly escaping death, he managed to save the drawings in his possession, but those of Wright\’s plans that had earlier been submitted to Faisal II and the ministry responsible for the work, the Development Board, were never recovered. Unlikely though it is that they could have survived the most recent carnage, it is a tantalizing thought. Echoes of them are also to be seen in the curvilinear design for the Grady Gammage Auditorium at Arizona State University, for Wright was quick to salvage at least some of his ideas.

The centrepiece of Wright\’s Baghdad project-nothing short of a new civic centre-was to be the Crescent Opera and Civic Auditorium. To be dominated by a ceiling shaped ‘like a great horn\’, the planned theatre would have a crescent-shaped proscenium arch, ‘to carry sounds as hands would be cupped above the mouth\’. A series of arches would have begun at the proscenium. Wright cited the Chicago Auditorium (now part of Roosevelt University) by his great predecessors Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan as another influence on the design: ‘the most successful room for opera and large audiences in existence\’, he called it. Flexible seating was planned, though the exact number of seats was never finalized. Various notes and plans show anything between 1,600 and 2,000 for opera performances, with the possibility of accommodating many thousands more on civic occasions. Some Islamic shapes-the crescent itself, and the mosque-recalling dome-were intended to make the building as inspiring ‘as any religious edifice\’, though it is hard to be sure how greatly that would have been appreciated by the distinctly secular and westernized clientele who would have used it. Still, the plans clearly mark the direction of Mecca. They also show a planetarium in the basement. The island was to have been landscaped with orchards and fountains, and would have been dominated by a 300-foot-high, ziggurat-like monument to Harun al-Rashid, intended to have a beacon effect comparable to the Statue of Liberty.

More puzzlingly, there is no indication of what might have been performed there operatically. Indeed, Baghdad never seems to have had much of an operatic life, certainly not compared with the ambitious seasons in Tehran in the late 1960s and early \’70s under the Shah\’s patronage. (The opera house that opened in the Iranian capital in 1967 was a much less original piece of architecture, modelled on the houses of Munich and Vienna.)

Wright\’s 1957 plan distilled an imagined memory of the ancient Abbasid city and went back even further to one of the oldest myths of mankind, the story of Adam and Eve. Quite apart from the political events that scuppered it, it was dismissed by modernist commentators at the time as an anachronistic phantasmagoria. But Mina Marefat (whose chapter on the Baghdad project in Anthony Alofsin\’s Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Beyond I gratefully acknowledge as the most useful source in researching this topic) persuasively argues that Wright\’s work stands as a valuable symbol today, by showing profound respect for the very cultural heritage to which the west can be hostile. ‘The functions of an opera house, a civic centre and a university were clearly modern ones,\’ she says, ‘but Wright gave them forms that linked them to the past and imbued them with didactic cultural messages, collective images shared by both east and west.\’ Though the realization of Wright\’s project would now be less imaginable than ever, it\’s worth pausing to remember than when America\’s greatest architect drew up a blueprint for Baghdad it was not chauvinistically western, nor an American attempt to destroy Iraqi culture. It was made in a spirit that future architects for the city might do well to study.

This article appeared in the January 2008 issue.