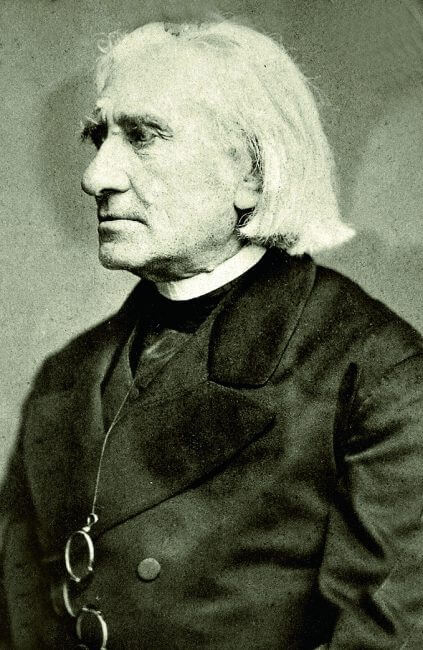

Liszt & the Opera: Arbiter of Taste

July 2011 in Articles

It is sometimes said, even by admirers of his work, that Liszt wrote no opera. The surprise caused by the discovery that this, in itself, is untrue is perhaps indicative of a common tendency to dissociate him from a form in which he had little compositional success, but with which he nevertheless had a complex relationship that in some respects was crucial to its development.

The piano pieces usually bundled together under the heading ‘operatic transcriptions\’ constitute a musical response to opera that lasted for most of his career. His association, meanwhile, with Weimar, first as Honorary Kapellmeister to the ducal court (effectively from 1848, when he settled in the town, to 1858), then (from 1869) in a less formal advisory role, is widely regarded as pivotal in the history of progressive aesthetics, and as having a formative impact on the work of Wagner, Berlioz and Saint-Saëns in particular. His range of interests and activities as a conductor, however, was wider than some have supposed.

As an opera composer, Liszt\’s career began and ended early. His only completed work in the form, Don Sanche ou le Château d\’amour, was first performed at the Paris Opéra on 17 October 1825, days before his 14th birthday. The choice of venue and the media circus that surrounded the premiere suggest an elaborate ploy on the part of Liszt\’s pushy father Adam, to market the 13-year-old prodigy as a second Mozart. Based on a tale by Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian (1755-94), Don Sanche deliberately evokes the late 18th century by lightly parodying ideas of chivalric love that go back as far as the medieval Roman de la Rose. The precincts of the Château d\’Amour may be penetrated only by those who love and are loved in return. Don Sanche can\’t get in, because his beloved Elzire wants nothing to do with him. Enlisting the help of the magician Alidor, he arranges for her kidnap so that he, in his turn, can pose as her rescuer, which produces the required emotional effect. The rococo dramaturgy includes a deus ex machina and ballet of Cupids, while the score-some or all of which was orchestrated by Liszt\’s composition teacher Ferdinando Paër-effectively consists of a series of genre pieces. The press was out in force on the opening night, and opinion was divided. The Journal des Débats described it as ‘cold, humourless, lifeless and quite unoriginal\’, though the Gazette de France prophesied that ‘nôtre petit Mozart en herbe\’ would go on to achieve great things. Don Sanche was not revived in Liszt\’s lifetime, however, and little has been heard of it since.

In the mid 1840s he turned to opera again. Both the ‘Faust\’ and the ‘Dante\’ symphonies derive, in part, from abandoned operatic projects: a stage work based on The Divine Comedy was on his mind in 1845; in 1850 he was considering an adaptation of Faust in collaboration with Alexandre Dumas, an idea to which he returned-this time with Gérard de Nerval as potential librettist-in 1854, the year ‘A Faust Symphony\’ was completed.

In 1846 he began work on Sardanapale, in three acts to an Italian libretto based on Byron: Liszt\’s correspondence suggests he was originally aiming for a Viennese

premiere the following year. In the event, Sardanapale was also abandoned. However, substantial sketches (111 pages) remain in piano score, enough to give us an insight into what a mature opera by Liszt might have been like. Bellini, Meyerbeer and Rienzi have been cited as the major influences, while the Petrarch Sonnets are reckoned to be the closest of Liszt\’s completed works to the opera\’s style.

With hindsight, we might also wonder whether the composition of a major stage work at the height of Liszt\’s career as a concert virtuoso would ever have been practicable. It is highly probable that by 1846 he was already considering a potential move away from the recital platform in a search for greater freedom as composer and conductor. His Weimar appointment, initially more nominal than actual, was both created and accepted in 1842; he conducted his first opera, Die Zauberflöte, in Breslau the following year; and sketches for some of his orchestral works can also be dated to the mid 1840s. His fascination, meanwhile, with Sardanapalus, the Assyrian king who sent the trappings of a glittering lifestyle quite literally up in flames, seems curiously prophetic of Liszt\’s own eventual decision to abandon stardom in 1847.

It is with Liszt\’s virtuosity that many of his ‘operatic transcriptions\’ are associated, which in turn colours the controversies that still surround them in some quarters. The form occupied him for much of his compositional career, and the works of most of his major contemporaries were subject to his pianistic scrutiny. Most of them are actually not transcriptions, and Liszt used such generic titles as ‘paraphrase\’, ‘réminiscence\’ or ‘fantaisie\’ to describe them. Some composers, notably Donizetti, Meyerbeer and, of course, Wagner, were grateful to Liszt for keeping their works before the public away from a theatrical context, and of his major contemporaries, only Verdi professed himself doubtful. Their origins in the elaborate extemporizations on popular themes favoured by many of the virtuosos of the period saddled them with a reputation for being vacuous show-stoppers, until such scholars and performers as Kenneth Hamilton and Leslie Howard began to unpick the assumptions surrounding them, and to argue for their originality and their contribution to the advancement of pianistic technique and expression.

There is no question that some were intended to astonish: it is impossible to listen to the Grande Fantaisie de concert on La Sonnambula, which wedges Amina\’s ‘Ah, non giunge\’ in counterpoint against Elvino\’s ‘Ah, perchè non posso odiarti\’ beneath a series of oscillating right-hand trills, without gasping at either Liszt\’s compositional cheek or the staggering technique required to play it, or both. Yet many also engage in a dialogue with each chosen opera that sometimes leaves us wondering why Liszt selected and re-fashioned the material in the way that he did.