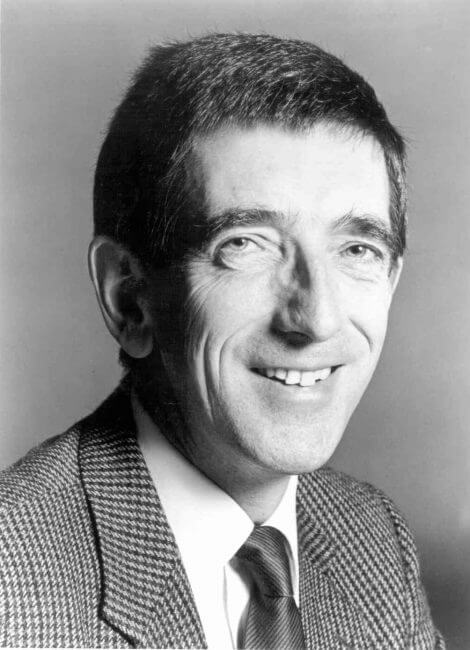

David Syrus celebrate 40 years at the Royal Opera

August 2010 in Articles

Yehuda Shapiro

The Royal Opera’s 1971-2 season, which opened with the Ring conducted by Edward Downes, featured Nilsson as Elektra under Solti, Vickers and Norman in Les Troyens under Davis, Caballé as Violetta, Verrett as Amneris, Pelléas under Boulez and Der Rosenkavalier under Krips; Kiri Te Kanawa broke through as Countess Almaviva and Plácido Domingo made his Covent Garden debut as Cavaradossi.

Another constant—if less headline-grabbing—musician also arrived: David Syrus, who joined the company as a répétiteur. He has remained at Covent Garden ever since, and for the last 30 years has been Head of Music (formerly Head of Music Staff). In this role, with a team of four plus freelancers, he is in charge of coaching for singers and the provision of rehearsal pianists, continuo players and offstage conductors. He also appears in the orchestra pit itself as a replacement conductor during the run of a production. Earlier this year he took over Fidelio and Die Zauberflöte, and over his time at Covent Garden has conducted works by, among others, Verdi, Wagner, Janáèek, Strauss and Tippett.

After four decades at the Royal Opera, Syrus, an unassuming man with an infectious passion for his work, remains idealistic about the art form’s possibilities, while casting a clear eye on its mechanics and priorities. ‘A composer has an idea, he has a text and then he makes the music. Performers have to follow that process too. A soprano who is offered Butterfly should read the Belasco play and the Illica libretto, and maybe listen to a recording to get an idea of the soundworld. She should certainly talk at home over breakfast about racial conflict and expectations of marriage in cultures. In practice, any soprano is first going to look at the score and check if she can sing the last few bars of “Un bel dì”. As a coach, my role is to prepare singers for the performance, and their dialogue with me is different from their dialogue with the conductor. I can’t tell Nina Stemme anything new about Fidelio, but I can pick up on details as I sit out front during rehearsals and performances. I might have to tell a singer: “Forget what the director told you and move across the table three bars earlier than you’re doing at the moment: your line isn’t coming through and I’m not hearing the harmony.” Or perhaps suggest to the director that the stage blocking is leaving a singer dangerously exposed at a tricky moment in a quartet. It’s part of our job to flag up potential problems, to be practical as a musician, and in some senses to fight for the singer. In an opera such as La Bohème, you find yourself spending far more time on the logistics of Schaunard’s entrance than on “Che gelida manina”.’

Syrus’s first experience of the Royal Opera House was in 1963, in the audience for Götterdämmerung under Solti with Nilsson, Windgassen and Frick. ‘These days, I wouldn’t necessarily like the way they did it, but it was high-quality virtuoso stuff, and the house singers of that era, like Marie Collier, made an impact on me. I can still hear her vibrato when she sang Gutrune’s line “Sie haben Siegfried erschlagen!”.’

A grammar-school boy from Hastings with a penchant for languages, Syrus read music on a scholarship at Oxford, then trained at the London Opera Centre before freelancing and auditioning for Covent Garden. ‘It was always a combination of languages, theatre and music for me, and, thanks to grants from my local authority, I received a variety of education. I didn’t have a great deal of training on piano, but I was facile on the keyboard and always got away with not practising too much. I was never a high-flyer who could master the Liszt Sonata, but solo pianistic skills actually aren’t important for this job. In a rehearsal, it’s a matter of conveying the right information about a piece through a strong sense of rhythm and dynamics and a certain amount of colour, of sketching in as much as the rehearsal needs, which also means knowing what to miss out. I like to keep my antennae out so I can analyze what the singer is doing, and also what the conductor wants. If I’m committed to getting all the double octaves in and worrying about what the second clarinet’s playing, I’m probably not going to be watching the conductor. If you don’t want to listen and assess, you probably shouldn’t be a répétiteur.’

It took no fewer than seven auditions (and an initial rejection) before Syrus was accepted onto the staff at the Royal Opera, following on from people such as Mark Elder, Jeffrey Tate and Roger Vignoles. ‘I didn’t have to play for Solti, who was in the process of leaving, though he was still Music Director. Ted Downes was there—he didn’t seem to like my playing at the time, but I became very fond of him over the years.’ In his first season Syrus prompted, coached understudies and played for rehearsals of one production, Billy Budd, conducted by Mackerras. His second season brought rehearsals of Owen Wingrave under Steuart Bedford.

‘In the third season I begged to play for a German opera, but first of all I had to audition by playing half of Salome for Maurits Sillem. It was a slow apprenticeship here, which suited me temperamentally. I’ve played as a rehearsal pianist for some wonderful people and have enjoyed close relationships with the last four music directors—Solti, Davis, Haitink and Pappano—who have all been very generous to me. In return, I’ve been prepared to work pretty hard—though Tony [Pappano] is way beyond the rest of us when it comes to work ethic, and he’s far more hands-on than his predecessors. Colin Davis took well to me after we’d initially had a strong disagreement—it turned out he liked some intellectual tension—and he invited me to Bayreuth, where I spent six summers between 1977 and 1984, and I also assisted him on recording sessions. Haitink is, of course, a wonderful musician, but he didn’t see himself as a natural for the compromises theatre can demand. He gave me a lot of freedom to put together rehearsal schedules and so on, and encouraged me to conduct.’