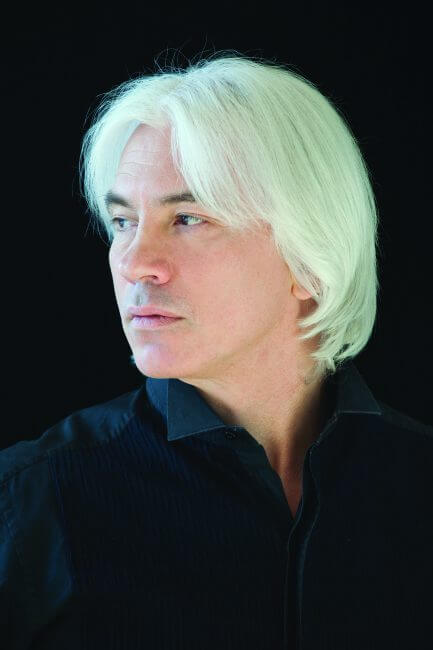

Dima Undimmed

November 2017 in Articles

Richard Fairman pays tribute to Dmitri Hvorostovsky

For an opera-lover it was one of those occasions when you always remember where you were at the time. I had missed most of the final of the 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World on television, but switched on just in time to catch a young Russian baritone sweeping on to the stage, looking full of confidence. His programme, ending with Rodrigo’s ‘Per me giunto’ from Don Carlo, was extraordinary. He had everything—the maturity, the nobility of style, and astounding breath control that stretched over two or three phrases, like an arching rainbow of beautiful tone. ‘That’s the winner,’ I remember saying to myself. ‘I don’t care what the others were like.’

That was easier to say, of course, if you had missed Bryn Terfel earlier. Dmitri Hvorostovsky later recalled how his confidence momentarily wavered after he heard Terfel sing and heard the response of the Welsh audience. ‘I thought that maybe, for the first time in my life, I was not going to win,’ he said, touching upon the arrogance of youth that had propelled him to Cardiff in the first place. But he did win, Philips and Decca were soon fighting over him (even though they were parts of the same company), and the doors of the world’s top opera houses were thrown open to him.

It might seem wearyingly predictable to open an appreciation of Hvorostovsky with memories of Cardiff, but how can one not? Nobody else in living memory has arrived on the international opera scene with such super-confident, awe-inspiringly gifted, totally knock-out elan. He was a star from day one.

Where did his artistry come from? Hvorostovsky credited his music-loving father, and an early start clearly helped—piano lessons from the age of 11, choral conducting in his teens, formal singing lessons at 16. At the local opera house in Krasnoyarsk there was no lack of opportunity and he had already sung Yeletsky in The Queen of Spades, Silvio in Pagliacci and Giorgio Germont in La traviata by the time he was 23. Yekaterina Yofel, the teacher who set him on his way and (crucially) taught him his amazing breath control, deserves to be world famous. She was ‘like a hypnotist’, he said later. ‘With her, even exercises have feeling.’ Like playing Bach? ‘Yes. Like Glenn Gould playing Bach!’

Much of his understanding of style he put down to listening to recordings in his early years. He loved Battistini (hurrah!), and the Russian baritone Pavel Lisitsian, so often overlooked in the West, was another favourite. It is easy to see why. Lisitsian’s long-breathed legato, so memorable from those dusty old Melodiya LPs, must have been quite an influence on the young Siberian. During an interview in mid-career Hvorostovsky explained why, saying that Lisitsian was still an idol: ‘He’s 90 years old now, and a friend of mine. He’s a maverick, a voice of Italian beauty, very smooth—you don’t see any stitches.’ Now that we are looking back, we can see Hvorostovsky as Lisitsian’s natural successor.

Hvorostovsky arrived in the West with one outstanding signature role in his luggage. I still remember his entrance as Onegin, his second role at the Royal Opera House—his youth, the flowing (not yet white) locks, the arrogant-looking stance and way of flicking the hair off his face. He was the right age for Onegin. He had the stature of an Onegin. He sounded like the Onegin of one’s dreams. No wonder he saw this as his ideal role in those early years.

As Russian composers generally gave their best male roles to basses rather than baritones, only two other prominent roles in the Russian repertoire suited him well: Andrey in War and Peace and Prince Yeletsky in The Queen of Spades. I was lucky to catch the latter at the Met in 1999—a tremendous cast headed by Domingo singing his first opera in Russian and with a late glimpse of the immortal Elisabeth Söderström as the Countess—and Hvorostovsky showed how his trademark long-breathed lyricism could shine even in a relatively small role against the most illustrious competition.

And then there was Verdi. Having shot to fame on the back of arias from Un ballo in maschera and Don Carlo in Cardiff, Hvorostovsky might have been expected to throw himself straight into the entire canon. But no—it was a mark of his career throughout that choices of repertoire would be made with circumspection. Giorgio Germont came early on, gratefully written for a baritone of Hvorostovsky’s mellow gifts, followed by Francesco in I masnadieri, which the Royal Opera took to the Edinburgh Festival, and Conte di Luna in Il trovatore. The heavier Verdi roles had to wait. No wonder his voice stayed fresh.

Take Lisitsian as your guide and it follows that when Hvorostovsky turned to Verdi, he would be an elegant stylist—more like the inimitable Battistini, or Bruson among more recent Italians, than singers such as the psychologically penetrating Gobbi or the vocal powerhouse that was Cappuccilli. It is fascinating to compare recordings of Lisitsian and Hvorostovsky. Lisitsian is the more instrumental, a pure stylist. Hvorostovsky, especially as he grew older, is the one who was searching for more meaning in the words, more colours in the voice.

I have lost track of how many times I saw him in Verdi. The Royal Opera featured him in Ballo, Rigoletto and Simon Boccanegra, in addition to the roles listed above, though not sadly in Ernani or Don Carlo, as the Met did. Whatever role he faced, he drew strength from the sureness of his technique and the artistic discipline of his singing—no barking, no forcing, no egregious effects. He was often criticized for being monochrome, probably by me, too. I feel guilty about that now that his artistry is no longer with us.

My only lasting complaint is that the top of his voice rarely opened out into the Italianate ringing sound that one ideally wants for Verdi. I see I was complaining about that right from the start, writing in opera about Hvorostovsky’s first Philips recital disc that the top notes of his Macbeth aria lacked brightness, as they had at his Royal Festival Hall debut concert a little earlier. I even wondered if he had peaked too early. Wrong about that then. A quarter of a century later he was still going strong.

His career followed a dignified path. I recall how people worried that the good-looking young star would be pushed into popular dates and crossover recordings, but Hvorostovsky defiantly set his own agenda. That meant following the high road of the great baritone repertoire in the world’s top houses, no cutting of the corners, no dumbing down, no selling his talent cut-price.

Other memories crowd in thick and fast. There was Count Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro at the soon-truncated season at the Shaftesbury Theatre during the Royal Opera’s redevelopment, when he entered, shirt half undone as though just out of bed, looking outrageously pleased with himself at the effect his entrance had, and going on to dominate the performance from first to last.

There was the Last Night of the Proms in 2006, when he serenaded the Promenaders with ‘Moscow Nights’, a performance sparkling with star quality. There were the tours in tandem with Anna Netrebko, both in top form when they dropped in at the Royal Festival Hall in 2010 (I wrote in the Financial Times that ‘Hvorostovsky pumped up the climaxes of “Avant de quitter ces lieux” from Faust with such pride in his top notes that it seemed the buttons on his skin-tight shirt might pop’).

And, last but not least, there were the many solo recitals, packed with songs by Glinka, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninov and, a personal favourite of his, Georgy Sviridov. Compared to the most celebrated of his Russian predecessors, Hvorostovsky was not as authoritative as Arkhipova, or as scaldingly unforgettable as the unique Vishnevskaya, but the combination of his dark, brooding baritone and his amplitude of style made him a highly satisfying interpreter of Russian song. He did not short-change his audience, either. Hvorostovsky would sing and sing, relishing every minute of being in front of an audience. Here was an artist who simply loved the business of singing.

What else could have kept him active right to the end? Look back on his unexpected appearance in the Met gala celebrating the company’s 50th anniversary at Lincoln Center in May last year, when the brain tumour that was to kill him must already have been far advanced. The occasion could have been heartbreaking, but it avoids that. He makes his way on to the stage unsteadily, but the voice still has its beauty, the singing its total commitment, and on his face the joy in performing is undimmed. So long as there are singers who love their art as much as Hvorostovsky did, opera’s future is bright.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, born Krasnoyarsk 16 October 1962, died London 22 November 2017.