Too Hot for the Bolshoy

July 2015 in Articles

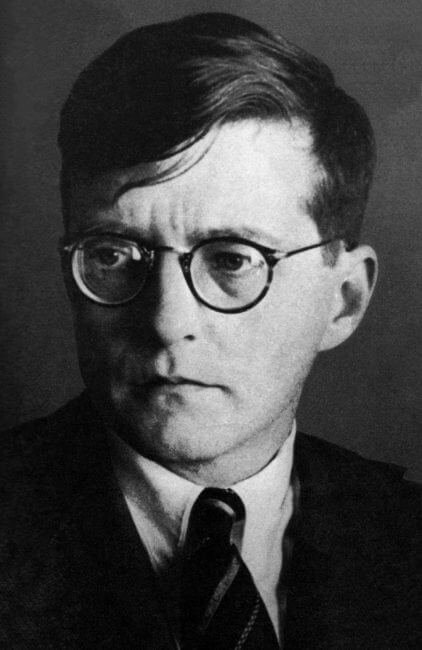

Martin Anderson on Shostakovich’s ‘Orango’

It might seem a bit of an exaggeration to claim that a single review could change the course of musical history. But when the ‘reviewer’ is Josef Stalin, and the ‘review’ the infamous Pravda article ‘Muddle instead of Music’, published on 28 January 1936, the result was indeed to derail the probable future of opera. The target of Stalin’s wrath was Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, a relentlessly inventive, hugely funny, darkly subversive burlesque. Anywhere else it would have raised the roof, and indeed it had already had some 200 performances in the Soviet Union, with three productions running concurrently in Moscow and other presentations abroad, before the fateful evening on which Stalin went to see it. The 29-year-old composer, on a concert tour when the article appeared, is said to have turned white when he read it; and over the next few weeks two more Pravda articles—unsigned, as the first had been—put the boot in again. Shostakovich was in terror of his life.

His first opera, The Nose, had been premiered in January 1930. Lady Macbeth had its first performance almost exactly four years later. Although The Nose didn’t enjoy the popular success that attended its successor, both works show Shostakovich to be an operatic composer in his bones: the music whizzes past in kaleidoscopic variety, the humour pointed, the command of pace and the sense of theatre absolutely assured. Still at the outset of his career, Shostakovich was set to become the 20th century’s operatic composer par excellence: in these two scores, and the many other stage works he wrote around the same time, he had established an operatic style that could have made him at least as influential as Berg. But after that reprimand in Pravda, apart from a satirical cantata that he kept well hidden and an operetta (Moscow, Cheryomushki) offering only mild social commentary, he completed not a single representational work in the remaining 39 years of his life, nothing that had a ‘meaning’ susceptible to political interpretation. In his ongoing game of cat-and-mouse with the Soviet authorities, everything else he produced could, if necessary, be explained away.

The recent discovery of the entire Prologue of a hitherto-unsuspected opera, Orango—to be premiered by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic this month—will reinforce the bittersweet sentiment piqued by those early displays of operatic brilliance. Salonen compares the ambivalence to the feelings that listening to late Mozart can stimulate—‘of course, he didn’t know it was going to be late Mozart’.

The origins of Orango almost make a comedy of errors on their own. The celebrations planned for the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution were intended to start early in 1932 and last throughout the year. Shostakovich had a lifelong habit of announcing works he ‘intended’ to write, which later became part of a survival technique whereby he would throw the dogs the bones they were expecting; but here he trailed an improbable number of works. In January the Leningrad Maly Opera Theatre announced a musical comedy with his music; and in February Shostakovich himself declared that he would be writing a five-movement symphony, ‘From Karl Marx to the Present’, and a comic opera in three acts. The Moscow Operetta Theatre then stated that Shostakovich’s Negro would be one of five operettas presented that autumn. And the Moscow TRAM (proletarian youth theatre) revealed that he would be involved in writing an anniversary march and in supervising a play with music. Whether he had the slightest intention of tackling this inflated ‘to-do’ list is unknown; all the while he was busy at work on Lady Macbeth.

Piling Ossa upon Pelion, in March the Bolshoy Theatre commissioned him to write the music for The Key, an opera to a text by Demyan Bedny, and strings were pulled to get him the manuscript paper he required—it was in short supply. But two months later Bedny threw up his hands, apologizing for the fact that he would not be able to supply the libretto in time. The Bolshoy administration, in a pickle through the loss of their star contribution to the celebratory events, looked around for another, and commissioned Alexey Tolstoy and Alexander Starchakov to write a libretto ‘on the theme of human growth during revolution and building socialism’. Shostakovich agreed to switch horses but, caught out by Bedny’s change of heart, insisted on receiving the libretto of the first act by late June, and the Bolshoy duly announced ‘a new satirical opera Orango’; it was ‘conceived as a political lampoon against the bourgeois press’. History then repeated itself, and Tolstoy and Starchakov failed to follow up their synopsis with the rest of the libretto, and so in October the Bolshoy management informed Shostakovich that his monthly fee was being halted. He put away his short score of the Prologue—the only part of the libretto he had been given—and turned to more pressing concerns. And so Orango passed into 80 years of silence.