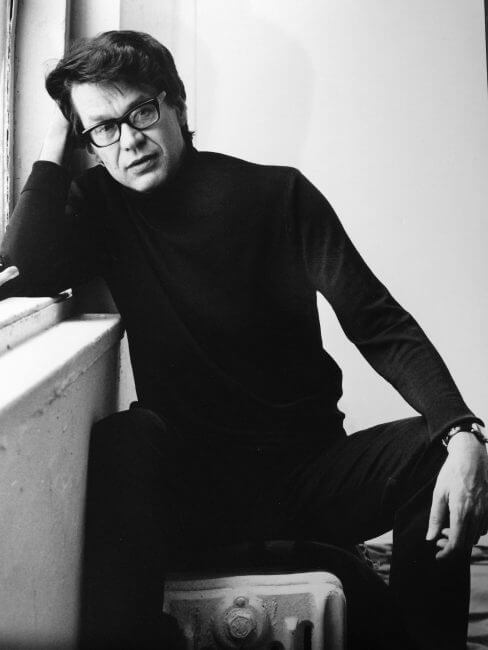

Andrew Porter, 1928-2015

March 2015 in People

Andrew Porter, the first of whose many contributions to Opera was published in the April 1952 issue (‘Opera and the Radio\’), the last in last month\’s, died in London on March 3 at the age of 86. Born (on 26 August 1928) and schooled in Cape Town, he was transplanted to Britain as a teenager, becoming Organ Scholar at University College, Oxford (1947-50), where he read English. Freelance reviewing followed for various London newspapers (including The Times and The Observer), leading to his engagement as music critic of, successively, the Financial Times, 1953-72, the New Yorker, 1972-92, The Observer, 1992-7, and the Times Literary Supplement, 1997-2009; during his FT years he also served as editor (1960-67) of the Musical Times.

His presence in Opera\’s pages never went missing for long, and took the form of longer essays in addition to those numerous shorter performance reviews. Indeed, Andrew\’s working relationship with Opera, under all four of its editors, proved in the end the strongest and longest-lasting of all-stronger still after his connection with the TLS was severed, and the ‘little magazine\’ became the only place where Andrew could regularly be read. In a final period rather less full of work satisfaction than the earlier years had been, this was at least a source of consolation.

It must certainly have remained a source of pride to Opera, given that for much of that working life-roughly two-thirds spent in England, one-third in the US-he was widely considered the leading music critic working in the English language. He was revered by both journalist confreres and those based in academe. A useful reminder of this came with Words on Music, the ‘Festschrift\’ published by Pendragon Press to mark his 75th birthday: its 20 contributing essayists, all of whom chose to write on ‘subjects of deepest concern to their colleague and friend\’ (in the words of the publisher\’s blurb), constituted an awe-inspiring roll-call of eminent music-writers alive at the time-Julian Budden, Winton Dean, David Drew, Philip Gossett, Daniel Heartz, Michael Kennedy, Joseph Kerman, Diana McVeagh, Jeremy Noble, David Rosen, to name but a few. (Opera\’s current editor and I both felt honoured to be invited onto the list alongside them.) In addition, three of the US\’s senior composers, Elliott Carter, George Perle and Ned Rorem, ‘composed special birthday greetings for inclusion in the volume\’.

Not many critics in any of the arts have been the object of such celebration. But Andrew was no less admired by ‘ordinary\’ music-lovers across the English-speaking world. Below all the newspaper and musical-journal obituaries, British and American alike, that I\’ve been reading online, the comment sections have been filled with touching salutes from readers recalling some peculiarly eloquent Porter phrase or paragraph directly inspiring them to broaden and deepen their own knowledge of the composers and/or performers he had been discussing. Critics are generally deemed marginal figures in and to any artistic experience-stimulating at best, destructive at worst, but by definition subsidiary, post hoc elements. Through his writing, but also through his many other achievements, Andrew established himself, particularly during his US sojourn, as not marginal but central: as someone who ‘made a difference\’.

It\’s been a formidable task, accomplishing this tribute to ‘the most erudite and perceptive music critic of his generation\’. The phrase is Nicholas Kenyon\’s, in the opening sentence of his finely discerning, precisely scaled and detailed Guardian obituary. In a moving New Yorker ‘Postscript: Andrew Porter (1928-2015)\’, Alex Ross, Andrew\’s successor music critic, went further: for him ‘Porter was the most formidable classical-music critic of the late 20th century, and, pace George Bernard Shaw and Virgil Thomson, may have been the finest practitioner of this unsystematic art in the history of the English language.\’

But of course Andrew was not just a music critic (and, it should be remembered, not just a critic of musical performance: his writings on the dance, during his Financial Times years and in the first part of his New Yorker stint, were similarly ‘erudite and perceptive\’ in style and content, inspiring similar admiration among ballet-lovers). He was also a scholar, translator, author of original opera librettos for the composers John Eaton (The Tempest, Santa Fe, 1985) and Bright Sheng (The Song of Majnun, Chicago, 1992), editor, lecturer (during Honorary Fellow stints at All Souls, Oxford, 1973-4, and at the University of California, Berkeley, 1980-81), radio broadcaster, and director of opera performance. In almost all these categories he distinguished himself, and in the first two he achieved wider fame-as discoverer in the Paris Opéra library of those many pages of Verdi\’s Don Carlos cut (but not destroyed) before its 1867 opening night, and as translator of 38 opera librettos into clear, singable English sensitive to overall ‘tone\’, keenly responsive equally to the composer\’s musical phrase and the librettist\’s original word. The range of these translations was quite as remarkable as the number: Mozart, Wagner (whose Ring became the most celebrated Porter work of all) and Verdi may have been the composers most frequently tackled, but there were also-and here I list no more than a random few-Haydn (L\’infedeltà delusa), Weber (Der Freischütz), Rossini (Il turco in Italia and Il viaggio a Reims), Thomas (Hamlet), Saint-Saëns (Henri VIII), Alfano (Risurrezione) and Strauss (Intermezzo, a particular tour de force originally produced for Glyndebourne and a leading lady greatly admired by Andrew, Elisabeth Söderström).

Having been in youth a continuo player-for Albert Coates in Cape Town-as well as organist, he possessed comprehensive command of the keyboard-music repertory, as became clear on those relatively rare occasions when he devoted newspaper reviews or New Yorker articles to the subject. (A memorable Observer phrase about Sviatoslav Richter in his last London recital-that the pianist had ‘touched a universal nerve\’-rings a bell in my head every time I play a Richter recording.) But his deepest involvement was with sung music, which he wrote about, in all its facets and branches, with what the late Stanley Sadie (in his ‘Porter\’ entry for the New Grove) defined as an ‘elegant, spacious literary style always informed by a knowledge of music history and the findings of textual scholarship as well as an exceptionally wide range of sympathies\’.

Those sympathies for sung music extended across the full length of western so-called classical music: described in summarizing shorthand, Andrew\’s range stretched from Peri and Monteverdi to an ABC-of-our-day of Adès, George Benjamin and Carter, not missing out nor lacking interest, at least in principle, in anything or anyone significant in between. This interest in so vast a ‘nearly-everything\’ was not just unfeigned but full-hearted, energetic and boyishly adventurous to the very end. In recent seasons his opera reviews of various Vivaldi rediscoveries in staged and concert performances manifested enviable freshness of spirit, an unfailing eagerness to enjoy the event in question, not just contextualize and comment on it. In that final opera review mentioned above, he could be found writing with characteristic economy of expression about Donizetti\’s still-little-known Furioso all\’isola di San Domingo performed by English Touring Opera at the London Hackney Empire, and about Donizetti and Malcolm Arnold rarities by students of the London Guildhall School.

Obviously, he didn\’t love everything. In a long 1988 interview conducted by the Chicago broadcaster Bruce Duffie (see http://www.bruceduffie.com/porter.html), he at one point attempted to ‘think of a composer whose work I don\’t admire but people go on playing. Yes-Boito\’s Mefistofele, a very popular opera. They go on playing this all the time, and what happens to me now every time I go is I think less well of it, and I don\’t think anyone is ever going to manage to persuade me that it\’s anything but the most inferior sort of opera-from a musical point of view.\’ But whenever he did respond, Andrew\’s verbal eloquence was invariably of the kind that left a profound mark on the reader. This is how, following a 1998 BBC-Barbican Martinů weekend series (which included a Greek Passion concert performance), he concluded a magisterial TLS Martinů essay at once copiously detailed, closely observant and raptly lyrical: ‘Martinů was promiscuous in his welcome-like that of any open-eared musician-of whatever he admired. He embraced the past. He composed in and for the present with uncompromising integrity, dreaming, yearning, hoping. His touch was sure, his ear fine-tuned, his mind eager. His life-infidelities to a loyal, supportive wife-seems to have been irregular. (But Berg, Janáček, and many another composer created great music from extramarital infatuation.) The cobbler\’s son was one of music\’s aristocrats, bountiful, eloquent, incapable of turning a dishonest, shoddy, or ill-considered phrase.\’ Who could read this, about a composer still too often patronized, not least for his compositional abundance, and not feel the urge instantly to scour one\’s CD shelves for whatever Martinů might be found there?

For myself, I owe Andrew a truly immense personal debt. This began nearly half a century ago. In 1969 I was a second-year music student at the still new, still under-equipped York University; I\’d rashly chosen Meyerbeer as a ‘special subject\’, only to discover that in the music library no Meyerbeer scores were to hand. Then I read in the latest Gramophone AP\’s long review of the just-released Decca Huguenots recording, and in desperation immediately wrote him a cry for help. Could I possibly come down to London at a weekend hour of his choosing and spend time studying his Huguenots score? The welcoming reply came quickly, an ‘Of course!\’ on a postcard plus a couple of suggestions for dates and times. That Saturday afternoon spent in his Kensington mews house sitting at a table surrounded by vast shelves groaning with scores and books and piles of books and papers on every available surface didn\’t just solve my immediate problem: it was the start of one of the most big-heartedly nurturing relationships I\’ve had. On my London visits he took me to contemporary music concerts-on one occasion we sat for hours on the floor at the Chelsea College of Arts while a very \’60s-style ‘happening\’ unfolded about us-and to a Covent Garden Wozzeck revival. I once babysat the nearby house of his sister Sheila, at that time Royal Opera press officer, while she was on holiday.

Further down the line, just as Andrew\’s New Yorker period was about to begin, he made possible an introduction to his FT successor, Ronald Crichton, which led to the start of my own career as a UK newspaper critic. In those years I sometimes felt like ‘Gesell David\’ to his prose-writing equivalent of Hans Sachs (receiving as I did regular letters close-typed on New Yorker notepaper in which, alongside brightly communicative bits of musical comment, chat and gossip, disapproval would be expressed of my FT sentences too heavily reliant on lengthy subordinate clauses-‘like an overfilled suitcase about to burst open\’). At no time, though, was he ever less than a dear friend, endlessly encouraging, with whom my wife and I spent many happy social hours. He could be moody, conversationally discontinuous, particularly in telephone calls, but also merry, high-spirited, above all-as all his closest friends knew full well-spontaneously affectionate and fine-grained in his sensibilities and emotions, and was altogether the most loyal and generous of ‘friends in need\’.

I\’m not by any means the only critic of a younger generation to feel this intense personal gratitude. After emailing the news of Andrew\’s death to Gillian Widdicombe, an ex-FT music-critic colleague and later the Observer Arts Editor who brought Andrew (and all his books!) back to London, I received a beautifully affectionate reply full of the same sentiments: ‘We were so fortunate to have Andrew\’s encouragement and affection. (Who else was so good a patron of the following generation? … ) It was impossible to emulate him, but so important to have that wry smile, or the little giggle as he pushed his specs up his nose, or the long pause on the phone followed by a quick, thoughtful burst of comment.\’

It saddened us both, I think, that those final London years turned out less of a golden autumn for Andrew than he thought or any of us hoped it would. The main reason is that during his transatlantic absence the Zeitgeist had changed. An independent-minded critic of his calibre, choosing to write at length about what he thought worthwhile rather than about what an Arts Page editor found buzz-worthy, unwilling to tolerate casual changes or cuts to his meticulously-punctuated and -structured copy, was not given the unlimited welcome in contemporary British arts journalism that he had had from William Shawn, the editor who had brought him on to the New Yorker. And in our day of Director\’s Opera, Concept Opera and those omnipresent ‘critical\’ stagings, his unswerving belief that opera production should reflect the ethics and aesthetics of Werktreue-the idea, as defined by (among others) the philosopher Lydia Goehr, that a work of art has a ‘real meaning\’ which can and should be established through faithful observance of its creators\’ notes, words and executive instructions-began to make him something of a critical outsider, even lose him a sympathetic hearing from certain younger opera appassionati.

Nonetheless, it was by no means all gloom: as I\’ve already indicated, Andrew\’s interest in new music, new operas, concert performances, student performances, rarity revivals, kept him going to the end. And what he has left behind-in those five volumes gathering together most of his New Yorker reviews; in the Opera archives; in thousands of FT reviews demanding collection-is an ideal of arts criticism given (as it were) verbal flesh. To borrow his own words on Martinů, Andrew was one of criticism\’s aristocrats, bountiful, eloquent, incapable of turning a dishonest, shoddy, or ill-considered phrase.