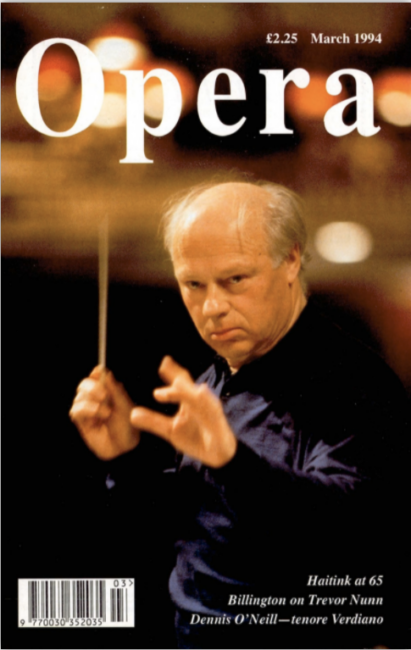

Bernard Haitink, 1929-2021

November 2021 in People

The death of the great conductor Bernard Haitink on 21 October 2021 represented — in many different ways — the end of an era. Opera audiences in the UK felt the loss especially keenly, since it was here that he enjoyed most of his operatic successes, first as music director of Glyndebourne and then at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden. Our obituary, published in the December 2021 issue, is prefaced with tributes from two distinguished singers who were close colleagues, the baritone Thomas Allen and soprano Felicity Lott.

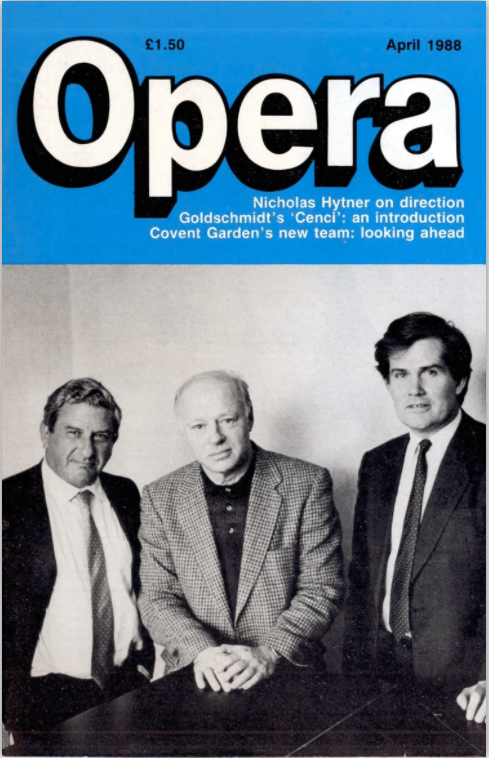

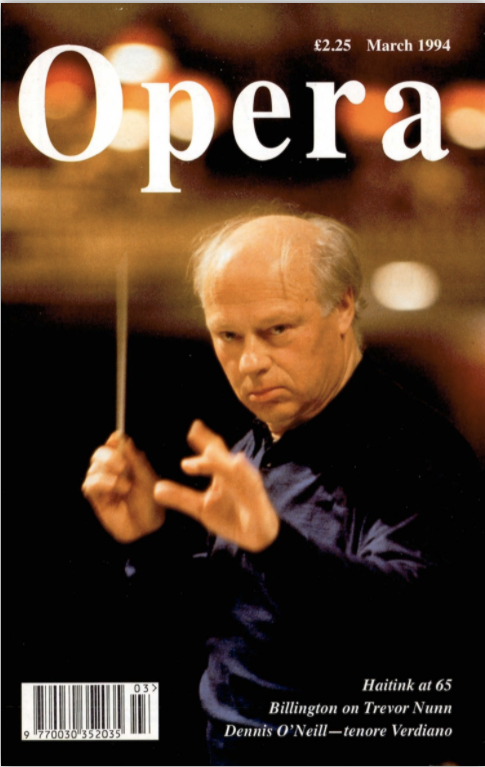

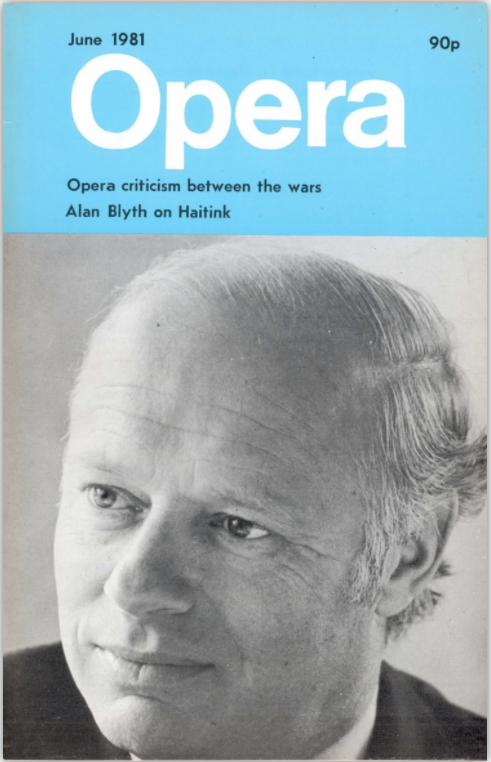

Explore Haitink’s operatic career further here with FREE archival access to features in the magazine, ranging from a first profile interview in June 1981, through an April 1988 conversation about artistic directions at Covent Garden and a 65th birthday tribute in March 1994 to the tributes on his departure from Covent Garden in July 2002.

Thomas Allen

It remains an insoluble mystery to me, that thing that happens when a conductor enters the arena to initiate a performance. I’ve watched with interest as the person in that role shimmies past many a valuable instrument and player to reach the first tee. What is in that person’s mind? From the moment of leaving the side of the stage, has the performance already begun? Is he or she already ‘in the zone’? When does the maestro decide that now is the moment to raise the baton, give a downbeat and cause the machine to start?

I watched Bernard Haitink, either as a member of the audience or as an anxious cast member in the wings, on many occasions. It was Meistersinger that engaged and intrigued me most, more so even than Don Giovanni. But whichever opera we were performing, I became aware of his greatness as he revealed to us the secrets of those scores over which he was master. Gently unassuming, often self-deprecating, he was the person who more than any other made me aware of what it is a conductor does out there. He was the architect and builder overseeing the gradual creation of immense musical temples.

In 1973 I worked with him at Glyndebourne on Die Zauberflöte, our first encounter. Back then he was anxious about the complexities of what needed to happen on stage, and became worried if everything didn’t go exactly to plan at the first attempt. That anxiety lessened with experience over the years, though I don’t think it ever wholly disappeared. On several occasions during the course of Don Giovanni stage rehearsals he became so engrossed in the action on stage during recitatives that he forgot he needed to take up the baton to initiate the next number. Such was his interest in the action, the play.

In a singing career spanning over 50 years, I was privileged to work with some of the greatest musicians of the day. My memories are many and very vivid, as one might imagine. But every time I worked with this quiet Dutchman there seemed to be something special in the air that took me by surprise time and again. Whether it was the whirlwind energy and brutal force of some of those Giovanni performances, or the wonderfully arching phrases of Figaro—all were special. But Meistersinger was the highlight: then he took us with him to Olympus.

We have his legacy, of course, in many, many recordings and films. But I’m left with the sad, sad thought that I will never again see that pale, unassuming figure make his way to the place he owned, where he made his music so magically.

Felicity Lott

My first memory of Bernard is seeing him at the far end of an audition room while I sang Anne Trulove’s aria from The Rake’s Progress. I was extremely nervous and he did his best to reassure me, telling me that everyone found auditions difficult. It turned out to be the only audition I did that worked, and it opened a whole new world to me. So my next memory of him is in rehearsals and performances of that opera at Glyndebourne in the brilliant John Cox-David Hockney production. It was so poignant to be in the audience for the Glyndebourne Tour’s performance of the same production, the day after hearing of his death. Gus Christie announced that it would be dedicated to his memory.

I shall always be grateful to Bernard for seeing something promising in that nervous beginner. I went on to sing with him so many times, as Pamina, Elvira, Octavian, Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Countess Madeleine in Capriccio, all at Glyndebourne, and later at the Royal Opera House as Countess in Le nozze di Figaro and as the Marschallin. His calm presence on the podium was benevolent and reassuring. I don’t remember any dramas or explosions: the orchestras always adored Bernard and he conjured glorious playing from them. He trusted them, and I felt he trusted the singers too—as long as we knew our music! He was precise and clear in the angular music of Stravinsky and spacious and expansive in Richard Strauss. Every performance was a special occasion with Bernard: we all wanted to do our best for him. I was the soloist in many orchestral concerts too, and our last one was at Wigmore Hall with the Nash Ensemble. We performed the Vier letzte Lieder and the final scene from Capriccio in a reduced orchestral version and I was so thrilled and honoured—I couldn’t believe it, actually—when Bernard said he would conduct. It was so extraordinary to share the Wigmore stage with him. The fact that he would accept to conduct such a concert speaks volumes about Bernard the man.

I wish I had been a more frequent audience member for Bernard’s concerts and opera performances, but I have vivid memories of some unforgettable performances, particularly Bernard’s last Prom. His shaping of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony was magisterial, and the outpouring of love, admiration and gratitude from the audience must, I hope, have warmed his heart. I hope I told him how much I loved him while he was there to hear it.

Richard Fairman

It was January 1996 and Bernard Haitink had asked to give an interview. It was known that life at the Royal Opera, where he was music director, was proving a trial, so maybe he had wanted to air his feelings about that, though I never did really pin down why. The company had recently completed Richard Jones’s much-vilified production of the Ring, which Haitink had hoped would crown his time there, and was entering a perilous and chaotic period prior to moving out of the theatre during its renovation.

Perhaps that was why he chose to be interviewed far away in Boston. He elected to meet backstage immediately after a Sunday afternoon concert of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 (it would not have been my first choice of timing if I had just conducted that symphony, let alone a performance of the finale as sublime as his).

This was the first time we had met, but Haitink’s reputation for being unassuming, even shy, had gone before him, so I was not surprised that he seemed reticent at the start. Was he thinking of leaving the Royal Opera when the prospects looked so miserable? He thought for a bit, hummed and hawed, and finally said he had not decided. (Not long afterwards, he did in fact resign in protest, but rescinded his resignation so that he could stay to support the musicians.)

Would he be happy then to stay in London? He paused for thought. The silence went on and on. Finally he conceded that he was pessimistic generally about the future for music in London, especially the self-governing orchestras, and slowly, haltingly, his feelings welled up. ‘Oh, it’s terrible!’ he said, slumping forwards in his chair, head down. ‘All the players can think about is the next day. They cling to what they have, always struggling on with the same battle for survival and the same misery. They are such good musicians and it breaks my heart.’

I was to learn at subsequent meetings that this was the true Haitink—no aggrandizement, no attempt to focus the conversation on himself, or his achievements, or what he might be up to in the future. Self-effacing to a fault, he wanted to talk only about his love for music and his concerns for the musicians who worked with him.

Some years later our paths crossed again in Dresden, where he was recording the Beethoven piano concertos with András Schiff, a near neighbour of his in London. The slow movement of the Third Concerto was on the music stands. A few brief comments were shared with Schiff and then the recording took place, no detailed instructions to the orchestra apparently being needed. Yet the recording has a marvellously rapt aura, which had come simply from his presence and baton technique. Insofar as the secret of his conducting style could be divined, here it was at work.

Haitink’s death at his home in London aged 92, on October 21, robbed the world not only of one of the leading conductors of the age, but also a wise and dispassionate man. Being in his company was always an opportunity to step away from the daily hubbub and think about life and especially music at a slower, more rewarding pace.

Born in Amsterdam on 4 March 1929, he spent the early years of his career in his native country, first as chief conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, and then for a prestigious 27 years as chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1961-88). A handful of opera productions in this period barely disturbed his focus on concert repertoire and Haitink himself did not rate them. It was only when he was already in his 40s that opera made a big impact on his life. ‘The theatre has given me something I needed badly,’ he said. ‘It has enriched my life incredibly.’

That enrichment began at Glyndebourne. Ensconced in the Sussex countryside, ‘free from the cares of the world’ as George Christie said in a eulogy to him, Haitink could hardly have found an opera company more suited to his needs. He also had the advantage of working with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, of which he had already been principal conductor for ten years. In return, he gave warm and deeply-considered performances that grew in their ability to tap the drama, especially in the composers that best suited him, such as Glyndebourne’s house composer, Mozart.

His second opera there was a turning point, the now classic David Hockney-designed Rake’s Progress, which Haitink said ‘made me realize for the first time that you could make real music in the pit in collaboration with the stage’. Two years later he became Glyndebourne’s music director (1977-87) and there followed a string of productions that rank among the most notable in the company’s history.

Together with the artistic director Peter Hall, he gave us a darkly Romantic Don Giovanni with Thomas Allen, Così fan tutte, Fidelio with Elisabeth Söderström, and the still-potent A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where he memorably used Britten’s orchestral preludes to probe Mahlerian depths. In visually stylish mode there were Der Rosenkavalier, with art deco designs by Erté, and the Hockney-designed Die Zauberflöte. Verdi was explored with Simon Boccanegra, La traviata and Falstaff. After he stepped down, he returned to open the new opera house with a Le nozze di Figaro (‘one listened enthralled’ said opera) that boasted Renée Fleming and Gerald Finley among the leads. So many successes, so few failures: no wonder many people look back on his time as a golden era.

Even so there was one crucial piece missing from the jigsaw. The old Glyndebourne was not big enough for Wagner, the opera composer that Haitink longed to tackle. His move to the Royal Opera, where he was music director for a still-longer period (1987-2002), was the climax of his operatic career, challenged by artistic and political controversies, hitting highs and lows beyond what he experienced anywhere else.

The greatest peak and trough (simultaneously) was the new Ring cycle. Richard Jones’s comic-strip production, with its Rhinemaidens in bubbly Michelin-man bodysuits, had few supporters and certainly not Haitink himself. A BBC2 fly-on-the-wall documentary called The House, which aired in 1996, captured the dismay on Haitink’s face as he was shown the collapsible car that was to be used for Fricka’s arrival. ‘What can I say?’ he sighed despairingly. It was the musical performance, and especially Haitink’s magisterial but always human conducting, that took all the applause. At the end of Götterdämmerung Jeremy Isaacs, the Royal Opera’s general director, tried to crown him with a laurel wreath, but characteristically he waved it away.

The happiest of his Wagner was Die Meistersinger, directed by Graham Vick and with a cast headed by John Tomlinson as Hans Sachs, about which he said, ‘We were just lucky to have all the right ingredients’. His Lohengrin was one of shining purity, but Parsifal, directed by Klaus Michael Gruber in 2007, was another botched shot (‘I’m sorry, but, you know, one closes one’s eyes and lives in the music’). A long-awaited Tristan und Isolde finally came in 2000 to mixed reviews (‘superb playing’, commented the Guardian, but the performance ‘never catches fire’).

Away from Wagner his fortunes were more secure. There was a superbly engaging series of Janáček operas—Jenůfa, Katya Kabanová and The Cunning Little Vixen—in which he found a wealth of warm-hearted humanity. There was much Mozart: sane, measured, never glib. He essayed Russian heavyweights including a much-prized Prince Igor and The Queen of Spades, and in English repertoire Peter Grimes and, unexpectedly, The Midsummer Marriage. His Verdi was up and down, wanting Italianate fire in Il trovatore, though the richer scores of Don Carlos (‘noble, sensitive, intent, very beautifully played’ said Andrew Porter in opera) and Falstaff drew a predictable glow. He wisely stayed away from the bel canto era and Puccini. Nor did he conduct Otello, as he said he could never match Carlos Kleiber, whom he heard conducting it at Covent Garden. Simon Rattle, in the box beside him, has recalled Haitink leaning across and saying, ‘I don’t know about you, but my studies are just beginning!’.

The main criticism of Haitink’s tenure at the Royal Opera was that a time of crisis demanded not just musicianship, but a leader. He was not ‘the boss in his own theatre, as Solti had been’, lamented Patrick Carnegy, the company’s former dramaturg ‘… and his effect on morale in general was not good’. Haitink reacted by keeping his head down in the score, but even he was finally pushed into a public statement when the board floated the idea of disbanding the orchestra during the period of the theatre’s closure. At the end of a concert performance of the Ring at the Royal Albert Hall, he spoke in public from the stage: ‘Thank you. You all know the situation. It’s desperate. Please help us.’

Aside from the youthful performances in the Netherlands, he conducted only sporadic opera outside the UK, including Fidelio at the Met, two Mozarts—Figaro and Zauberflöte—at Salzburg, and a late Tristan in Zurich. The July 2002 issue of opera includes an affectionate array of tributes for his operatic achievements.

After he said goodbye to opera, Haitink enjoyed nearly two more decades conducting the world’s top orchestras. He held posts with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Staatskapelle Dresden and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and late in his career surprised everyone with his root-and-branch rethinking of the Beethoven symphonies with the London Symphony Orchestra.

His career coincided with the peak of the classical record industry, so his art can be revisited on countless recordings. For the man himself, look out John Bridcut’s recent television documentary, Bernard Haitink, the Enigmatic Maestro. Towards the end Haitink talks about his childhood in wartime Amsterdam, reflecting on the deprivation and the worry of Jewish lineage on his mother’s side. As he speaks in his measured tones, the feelings almost reluctantly allowed to resurface from deep within, the real Haitink is revealed. The last half-hour is very moving, a memorable tribute to a much-missed man.