One eye wet and one eye dry

April 2022 in Articles

Great singers in great roles: Felicity Lott talks to Jon Tolansky about the Marschallin

Just as Clytemnestra should not be an old hag but a beautiful proud woman of 50, whose ruin is purely spiritual and by no means physical, the Marschallin must be a young and beautiful woman of 32 at the most who, in a bad mood, thinks herself ‘an old woman’ as compared with the 17-year-old Octavian. (Richard Strauss, 1942)

Before voicing his strong reservations about many interpretations of Baron Ochs (without mentioning any names), Strauss goes on to warn that the Marschallin must not ‘play the end of the first act sentimentally as a tragic farewell to life but with Viennese grace and lightness, half weeping, half smiling’. Significantly, he again refers to Viennese sentiment at the end of the essay: ‘Viennese comedy, not Berlin farce’, he admonishes, talking about the way he has often seen and heard Ochs’s first scene in the Marschallin’s bedroom come across. As we hear in the way Strauss conducted his music and also played his song accompaniments on the piano, he always favoured subtle statement rather than melodrama, and that is precisely the quality for which Felicity Lott has been so highly and widely praised in her interpretations of the Marschallin. Capturing so many shades of subtleties vocally and theatrically, she has triumphed in the delicate balance between controlled but deep emotion and resolute but compassionate graciousness that this most radiant but also profoundly poignant role requires. She was Carlos Kleiber’s very favourite Marschallin when she sang the role with him in New York in 1990 and then in Vienna in 1994 (captured on DVD). By that time she had sung it many times in many productions since her first Marschallin in 1986 at the reopening of La Monnaie in Brussels in a production by Gilbert Deflo, conducted by John Pritchard. However, that was not the first time she had sung in Der Rosenkavalier. That had happened six years earlier, in 1980, when she had sung Octavian (often assigned to a mezzo-soprano) at Glyndebourne in John Cox’s production. And so, fascinatingly, on stage she first experienced the Marschallin through Octavian’s eyes.

FL: I loved that production and it was wonderful to sing that role. Altogether I think I did about 30 performances. I suppose at the back of my mind I thought I would love to be the Marschallin, but I had a whale of a time singing Octavian. Looking back now, I think that when I did come to sing the Marschallin, I had been able to consider a particular perspective on her coming from Octavian’s viewpoint. By then, if Octavian didn’t behave in the way that I thought he should, or shall we say in the same way that I had, I found that difficult, and in fact upsetting. The point is, though, that when I first performed the Marschallin, a lot of the ideas that came to me about how she reacts to Octavian had been seeded in the relationship between her and Octavian that I had been a part of from Octavian’s side. For instance, experiencing the Marschallin in the trio at the end of the opera from Octavian’s place increased the need to be really controlled when I was the Marschallin. As Octavian I was holding back tears—I couldn’t believe how wonderful and generous this woman was, and I actually found it tremendously difficult to leave her for Sophie, who of course he is in love with—the guilt of letting down this woman who had given him so much. So when I came to sing the Marschallin, for me she was particularly aware of Octavian’s feelings here, and that meant I had to be even more in control of myself. It must not be a sentimental wallow, or it is ruined: it’s one eye wet and one eye dry. Actually the hardest part of all for me was when she comes back very briefly with Faninal after she has left Octavian and Sophie to be alone together. It’s quite devastating to play at that moment: when Faninal says ‘Look how they are when they are young’, and she just says ‘Yes … yes’. And then you have to pull yourself together and go off grandly with your head held high. You must be in control—she is an aristocrat and she would carry herself off without indulgence. She’ll cry when she gets home, but not here—and that’s tough to do!

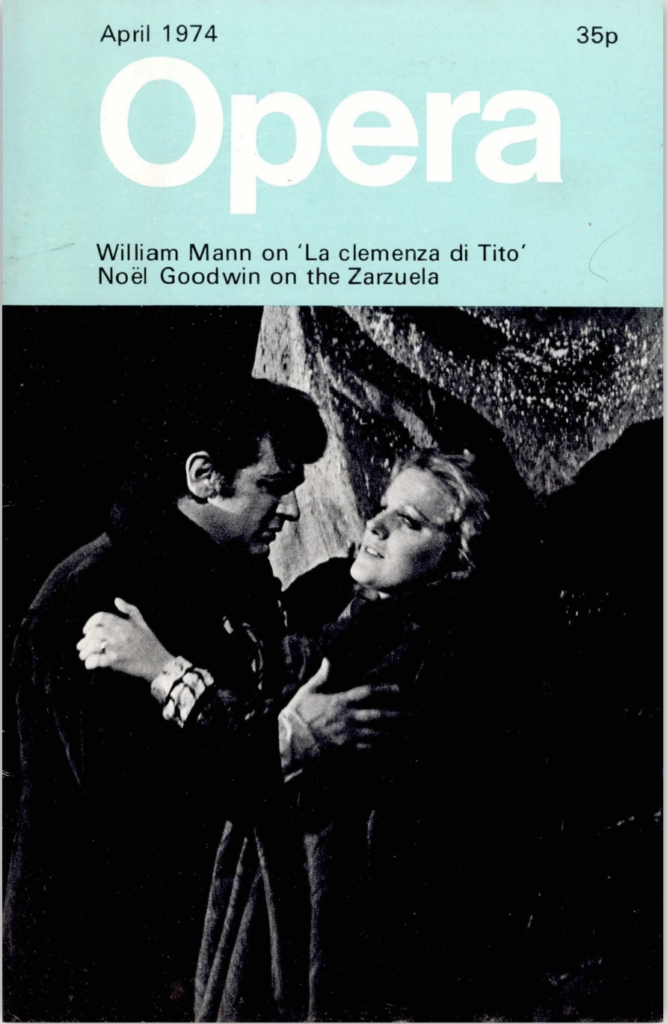

‘Der Rosenkavalier’ at Glyndebourne in 1980

JT: When you say ‘one eye wet and one eye dry’, you bring to mind how Strauss himself said the Marschallin is half weeping and half smiling in her Act 1 monologue. I know that’s a very different situation from the end of the opera, but I think you are reflecting his concern that as an aristocrat she must not be played sentimentally.

FL: Well yes, very much so, and even in that monologue one has to be self-controlled for that very reason, because it is an emotional scene. When she sings ‘How can it be that I was the young girl and I will be the old woman, the old Marschallin, and I am still the same person?’, you really do have to be careful not to be over emotional, most especially as Strauss has written that passage so delicately, and with such mystery. Even though she is still young, what she has to say there about ageing is universal for everyone, not just her, and it’s so brilliantly expressed by both Hofmannsthal and Strauss. I was getting on for 40 when I first sang the role, and it didn’t seem quite so poignant as it does now, but I still found it very moving then: how can it be that I was this young girl and I am going to be this old bat? Now today, after saying that to myself year after year, as it’s an opera that I’ve lived with all the time since I sang it, I realize more than ever how, yes, you are the same person inside however old you are. I am sure Strauss was aware of how easily the singer could fall into being maudlin at that moment, and he had probably seen that happen, so in his comment he was warning against it as she is indeed a young woman—and self-restrained as an aristocrat. And I think it’s because this lady who is so graceful and noble in spirit sings about this as a young woman that everyone in the audience, young and old, identifies with her. We all have that experience in life—whatever cases we build around ourselves and facades we erect to cope with life we are still the same person inside. Which is awful, but wonderful.

JT: Taking a cue from Strauss’s comment about how much older she is than Octavian, that ramps up her awareness of time and ageing, even though she is young. And so her musing there is particularly poignant when we remember the opening scene with Octavian when Strauss writes music for her to be just as a woman with a much younger lover would be, as though she is a lot younger than she really is.

FL: In that opening scene I always used to think she is having such a wonderful time particularly because she is with someone who is so much younger than she is—she is in love, and he is so young, and she feels she is a girl again. You almost have to sing like a girl, even though she is 32, as Strauss writes these frivolous phrases, almost like teenage phrases, in the music. She wants to be girlish with Octavian—how wonderful for this mature woman to have a young man who is so besotted with her—it must be great! But of course at the same time, as an experienced older woman would do with a lover of his age, she is showing him ways of making her happy—almost teaching him how to be a finer lover. It’s a very fine balance in that scene—she adores having Octavian as her lover, and yet at the same time she is being so gracious to him. And so later on, after she has had the business with the levée and all those wretched people trying to sell her things, and Ochs being so awful, chasing Mariandel/Octavian and ignoring her in her boudoir—after all this ghastly stuff has gone away she is left alone and finds herself starting to think about time, so now she’s miles away from where she was in the first scene with Octavian. And then when he comes bouncing in like a great big excitable labrador panting ‘Here I am, love me, love me’, she just wants to read a book or something. And of course that’s a shock to him.

JT: And yet in the scene that follows, which in many ways is a painful discourse, Strauss again has written in a deliberately understated way for the Marschallin—to avoid melodrama, do you think?

FL: Well, surely it’s because the Marschallin also is sad here but she must not be showing the real reason for her sadness to Octavian—that she knows that her affair with him cannot last. And again it’s so very important to be really in control here, because it is emotional for her and she knows the danger of that. When she tells him in quite a calm way that he will leave her one day in the future, of course he takes that badly, and that’s very difficult for her to bear, but she must keep her dignified control, even though she is upset. And when she sends him away I don’t think at all that it’s for ever—she just wants to be on her own and have a bit of time to think. Then she realizes she hasn’t handled him well and feels bad about it. So there’s a great deal going on there—a great deal beneath the surface for the Marschallin.

JT: Strauss in his typically down-to-earth way referred to the ‘somewhat talkative text’ of Der Rosenkavalier, which surely is one of its great lifelike joys. I think that, rather like with Falstaff and La Bohème, this is a particularly critical issue when it comes to the interplay between the singers and the conductor—or maybe the other way round—ideally a spontaneously free yet tightly precise one all at once. You were Carlos Kleiber’s chosen Marschallin both at the Metropolitan Opera in 1990 and the Vienna Staatsoper in 1994. How did you find the interplay?

FL: He knew every word and every nuance of the entire opera—and, to answer your question, he had a way of giving you time but not too much! He held it all together marvellously. He didn’t want any unnecessary hanging about or lingering, but then when you needed space it was always there. For me it really was the most wonderful experience singing the opera with him, both in New York and in Vienna. I felt that he absolutely captured what you were referring to—uniquely so, I think, at least in my experience.

JT: What was it like auditioning for him?

FL: He came to the dress rehearsal of Der Rosenkavalier when I was singing the Marschallin at Covent Garden in 1987, and when I went back to my dressing room at the end of Act 1 this chap in an anorak came round and said ‘Hello, I’m Carlos Kleiber. I really liked your performance, congratulations. Maybe we could do the opera together some time?’ And the next time we met was for the rehearsals in New York three years later. So that’s what it was like auditioning for Carlos Kleiber. But then of course he was tremendously demanding about all the details, and he was there for every rehearsal—all the stage and piano rehearsals as well as the orchestra and stage ones.

JT: One of my former colleagues in the Royal Opera House orchestra told me that when Kleiber rehearsed Der Rosenkavalier there—for his debut—in the summer of 1974, at one point he said to the players that the Marschallin needed a delicately airy accompaniment like an exquisite lady gliding in a flowing dress, because she is so subtle.

FL: I do like his analogy! And he was absolutely right about her character. Often she suggests something subtly rather than dwell on it factually, as it were. I did love that about her, and I did feel very much at home being her in that way—being gentle but strong too. At the same time, because you have to be strong and controlled, I did find the beginning of the final trio terrifying, especially with Octavian’s ‘Marie-Theres’!’ right before the Marschallin sings. It’s very upsetting to do, but you absolutely mustn’t look or sound upset, not openly so—not to Octavian, or Sophie or the audience. You have to put across that you are a person who makes everything right with great grace and charm, and that it does actually cost you and that you are in pain—but that you don’t show it, at least not conspicuously, if that makes sense. You kind of go into another world of slow motion for this trio because after her conversation with Sophie, which is real and almost casual—‘And maybe my cousin will bring some rosiness to your cheeks’—now her personal relationship finishes as it were, and while Sophie and Octavian have their thoughts together, she sings to herself about how she always vowed to love Octavian in the right way—that she would love his love for another woman—but she didn’t think it would happen so soon. It’s a huge sudden change, and when that almost wobbly chord sounds deep in the orchestra just before Octavian’s ‘Marie-Theres’!’, you have to be completely prepared and controlled to be able to handle it.

JT: You have taken part in a very varied selection of productions of the opera—has that been challenging?

FL: In fact some of the productions I have enjoyed most of all have been updated ones. Both the Met and Vienna productions were old style, and they were very good, but I did especially enjoy singing in Adolf Dresen’s production at the Châtelet Theatre in Paris and also Jonathan Miller’s staging which I sang in Madrid. I think in that production I felt liberated by wearing elegant modern clothes rather than those big frocks—you move differently, more naturally when you are wearing more contemporary costumes. The hardest part for me in that performance was what I had to do for Jonathan Miller at the end of Act 1. After I had finished singing I had to go to a desk … take out a cigarette … flick the lighter … take in the smoke … and blow it out on that last violin note. I can’t tell you how difficult it was to time that. It was harder than all the singing!