John Adams’s new opera Antony and Cleopatra

September 2022 in Reviews

San Francisco

In a telling, vividly realized scene in Act 2 of John Adams’s new opera Antony and Cleopatra, Caesar (the transfixing tenor Paul Appleby) unleashes a mighty polemic to a rabid Roman throng. Here, in an inspired fusion of action, propulsive music, language and spectacle, the work tightens its fierce grip on the audience. Massed downstage to sing the concussive chords that make up Adams’s ‘vox populi’ cries of affirmation, the chorus merges with a sepia-toned projection of an even larger milling throng. Appleby’s Caesar delivers his calculated power-grabbing speech from a brightly lit window that opens, as if by some gravity-defying feat, high above the stage floor. As his declaration of absolute authority pummels onwards, Caesar’s gigantically enlarged face appears in multiple projections, as if at some present-day political rally.

Adams and his collaborators—the director Elkhanah Pulitzer and a splendid design team—don’t need to underscore the resonance of the moment, which carried a perversely thrilling charge at this, the opening performance of San Francisco Opera’s centennial season (September 10 at the War Memorial Opera House). At this crucial juncture in the opera’s appropriation of Shakespeare’s 1607 tragedy, a leader’s hold on his bedazzled followers obliterates the chess game of diplomacy that has enmeshed Caesar, Antony (the affecting bass-baritone Gerald Finley), his Egyptian consort Cleopatra (the penetrating soprano Amina Edris) and numerous aides and attendants. Caesar, his base fully mobilized, has anointed himself Emperor. The poisoned stench of authoritarian fascism is in the air.

Lasting three hours and 20 minutes, including one intermission, Antony and Cleopatra rises to various peaks, in different emotional keys. The opening scene, with a hungover Antony lounging in a scoop-shaped bed in Cleopatra’s Alexandria boudoir, has a louche sensuality with a clawing undertow signalled by the angular shards of the orchestral writing. Later, with Antony back in Rome to negotiate with Caesar and assent to a politically expedient marriage to Octavia, Caesar’s self-effacing sister (the sturdy mezzo Elizabeth DeShong), Cleopatra laments his absence poolside back in Egypt. The scene had one of the evening’s few laughs, albeit a dark one, when Cleopatra cuffed around the hapless messenger (Brenton Ryan) who brought news of Antony’s marriage. In the opera’s expressively understated climaxes, both of the title characters’ death scenes were movingly acted and sung.

And yet, as boldly conceived and exitingly staged as it was, this premiere proved doth dramatically daunting and musically wearying in stretches, especially through the first act. With its crowded narrative and the predominance of Shakespeare’s Elizabethan verse (along with borrowings from Plutarch, Virgil, and others) in Adams’s own libretto, the supertitles draw an outsized share of the audience’s focus. Even then, some of the events, such as Cleopatra’s tricky naval manoeuvres, left some opening-nighters asking each other if they knew what had happened.

While a beat-by-beat grasp of the plot isn’t strictly necessary on a first listen (think of some of Handel’s mind-twisters), the music should fully engage. While the score is full of brooding orchestral colour, with the basses, trombones, tuba, and timpani figuring prominently, it too often felt punishing and brawny to a fault. And while writing for the voices ranged from oracular to intimate, there was only one short duet, and not enough that lingered in the mind. Yet in the stronger second act the tonal palette grew more delicate, yearning and alluring. In one striking touch, a repeating harp figure floated over Cleopatra’s voice like a ground bass lofted into something ethereal.

SFO’s music director Eun Sun Kim conducted with clarity and vitality. Appleby, Finley and Edris (replacing Julia Bullock, who withdrew due to her pregnancy) were all persuasive in the principal roles. Others in the large cast of supporting roles acquitted themselves well.

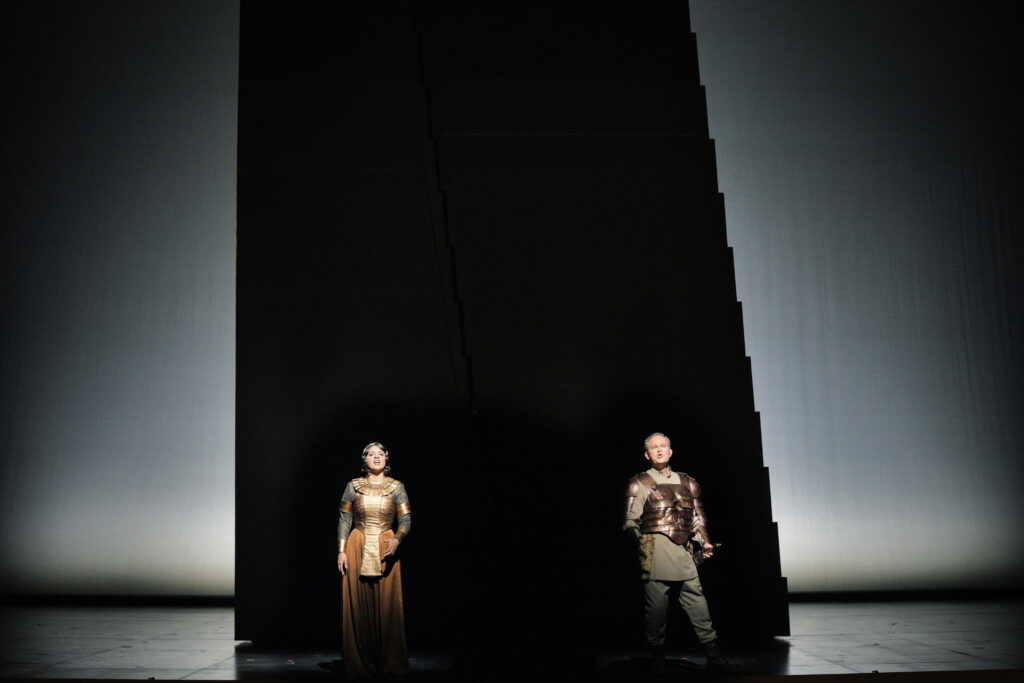

Mimi Lien’s set used sliding walls and apertures to achieve a cinematic flow across the nine scenes. Bill Morrison’s projections and David Finn’s lighting added a sense of movement through time and space, from the stark and sensual Egyptian geometries to the urban clamour of Rome, from a doomed love story to the preening power of the rulers.

Adams—whose previous works Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer and Doctor Atomic are milestones of the operatic repertoire—said in a programme interview that he saw a clear through line to those earlier works. Calling Shakespeare’s tragedy ‘uniquely and psychologically modern’, he noted that ‘despite its ancient source and setting, it is an apt companion’ of the contemporary or recent scenarios of Nixon, Klinghoffer and Doctor Atomic,all three of them collaborations with the director and sometimes librettist Peter Sellars. That said, this is a clear departure for Adams, a venture into a complex historical narrative that both taps and tests his resources.

Few operas are finished products on first arrival. A co-commission and co-production with the Metropolitan Opera and the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, Antony and Cleopatra has room to find its best and most fitting contours in the months and years ahead. As always with a work by John Adams, attention must be paid.

Steven Winn