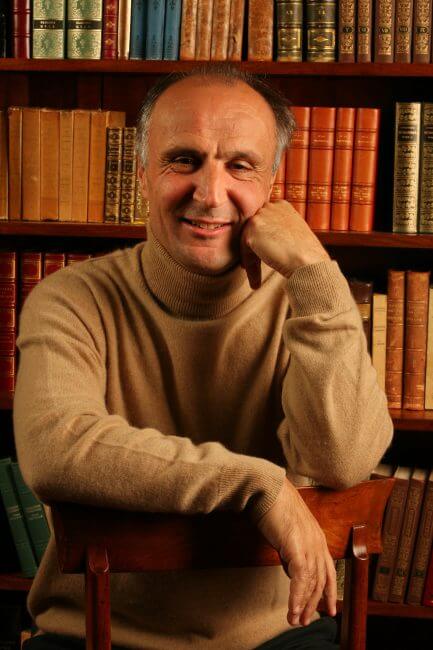

Oleg Caetani

July 2016 in People

No, says Oleg Caetani, he does not feel he suffered an injustice in the fact or manner of his removal as music director-designate of English National Opera in December 2005, barely ten months after the appointment had been made. And yes, he is delighted to be back at the Coliseum to conduct Madam Butterfly. ‘ENO did everything to please me,’ he says of this month’s revival, ‘granting me the cast I wanted and the right quantity of rehearsals. I love this orchestra and chorus. They are very special.’

Given the way Martin Smith’s board of directors treated him in 2005, most conductors would have vowed never to return. Caetani took no umbrage and moved on. As many opera houses and orchestras around the world have discovered, he is a law unto himself, which has its good side—manifested in his ‘no-hard-feelings’ regard for the company with which he made his UK debut. As his two ENO appearances, Khovanshchina (2003) and Sir John in Love (2006), demonstrated, Caetani is one of the finest theatre conductors today, with a flawless technique, an eclectic repertoire (65 operas) and a quality of musicianship that, at its graceful and expressive best, raises the spectre of Carlos Kleiber. As ENO music director, he would have been a massive gain for London.

But like Kleiber, Caetani has paid a price for his gifts. He shows no interest in a conventional career and has been known to make artistic demands that suggest unrealistic expectations. That is probably why in 2009 he abruptly parted company with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, of which he was chief conductor, just as it was about to release an excellent cycle of Tchaikovsky symphony recordings they had made together. It may also explain why Caetani regularly works in the Far East but has no American engagements. Prior to this month’s Butterfly, he had not conducted any opera for a year, and he has no other plans for theatre work in the foreseeable future. By most standards of evaluation, that must rank as a tragedy.

Perhaps Caetani’s standards are too high for the rough-and-tumble of everyday musical life. Perhaps he has been badly advised. He has no agent, preferring to channel the business side of his life through his Italian wife, Susanna, a former concert pianist. The most likely explanation for Caetani’s hit-and-miss career is that he lacks the burning ambition to conduct the sort of top-notch, career-defining ensembles that his talents would justify.

Asked to explain himself, he refers to Bright Star, Jane Campion’s 2009 film about John Keats, in which the poet, lying on his deathbed, is told some of the wonderful things that have been written about him and his work. ‘And he asks in a very naïve way: “Is that a success?”, as if to say it doesn’t mean anything to him,’ says Caetani, 55. ‘Well, I am not Keats, but I have got a lot back from my work. The fact that I have not had more does not make me sad. It is important for an artist to evaluate the beautiful things he has. I love working in Japan. I love working at ENO. When things happen, I enjoy them enormously, and I also enjoy them afterwards [in recollection] for the experience they gave me. So I can’t say it is a tragedy that I didn’t conduct the leading orchestras of Berlin, Chicago and Boston. If it comes, it comes. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t. Music gives you so much. If I had a bad relationship with my wife or children, that would be a tragedy.’

Caetani, who lives in Florence with his wife and seven-year-old daughter (he has two older daughters by a previous marriage), was born in the Swiss city of Lausanne on 5 October 1956. His father was the Russian-born conductor, composer and teacher Igor Markevitch (1912-83), who grew up in Paris, worked with Serge Diaghilev, Leonid Massine and Serge Lifar in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and later counted Wolfgang Sawallisch and Alexander Gibson among his conducting pupils. Caetani’s mother (Markevitch’s second wife) was Donna Topazia Caetani, a Florentine with whom Markevitch had settled in Switzerland, and who had family connections in Brighton—the source of Caetani’s lifelong love affair with England. At the age of five, when his parents departed on a long tour, he was sent to the Brighton family for three months. Several subsequent summers were spent there—‘among the happiest times of my life. That’s when I learned to speak English.’

French is his mother tongue, but he is equally fluent in Italian, Russian and German—all of which cultures played an important part in his education and the development of his repertoire. By his own admission Caetani’s boyhood was a ‘gypsy life’. He grew up in the Swiss Alpine resort of Villars. When Donna Topazia separated from Markevitch and moved back to Lausanne, the ten-year old Caetani was sent to boarding school in the Pyrenees. Then, from the age of 15, he attended school in Nice. At 18 he knew he wanted to dedicate his life to music.

His sense of mission is hardly surprising. He had started composing as a child and at the age of nine was introduced to the legendary Nadia Boulanger, one of his father’s Parisian associates, ‘who believed immediately in my talent and insisted I must study music. My parents didn’t want me at that stage to immerse myself in music, so I did my baccalauréat, but every summer I studied with Boulanger at Fontainebleau, where she had an American Academy—huge rooms filled with pianos. All my musical impulses came from her: she took care of me and had a great impact.’

Boulanger is best remembered as a teacher of distinguished composers, Aaron Copland and Elliott Carter among them, but Caetani saw her as having the personality of a conductor. ‘She was like a female [Yevgeny] Mravinsky [the long-serving conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic and close Shostakovich collaborator]. She had a great feeling for tempo. At her famous Wednesday lessons at home, if a pianist played anything in a tempo she didn’t feel was on the spot, she would conduct him with such a clear gesture. It was she who gave me an artistic ethic—the seriousness and freedom I have today. It was her whole approach: she knew the academic foundation was extremely important, but at the same time she knew music had to be free. She would ask, “What do you want to do today—a lesson in harmony on septachords? Or do you want us to listen to Stravinsky’s Mass?” We’d listen, and she would explain it and then she’d say, “Read it and play it on the piano for me.” It was a struggle, and with huge patience she would wait till I finished. She taught me to enjoy music but to work hard on it too—both together. She was a loving person, not as strict as her “Madamoiselle” reputation would suggest, and very open—she was fascinated by Boulez, Stockhausen and Xenakis.’

Mention of Boulanger’s ‘artistic ethic’ brings Caetani back to the question of career-building, a concept in which he clearly has no faith or interest. ‘I see my job as a luxury. I don’t believe I should have to make sacrifices for the sake of a career, but I do believe I have to enjoy my music and work hard on it. So when I hear that I should make this or that move in my career, or conduct an orchestra or a work I don’t like, in order to reach the next point in the strategy, it means nothing to me.’

Small wonder that leading artists’ agents shrug their shoulders when you mention Caetani’s name. But—getting back to the things that make him tick—what of his father’s influence? Thanks partly to a busy international career, Markevitch had minimal contact with his son and showed little interest in his musical progress until, aged 13, Caetani visited one of Markevitch’s masterclasses at Monte-Carlo. ‘I was following with a pocket score and on one occasion I asked him if I could conduct. It was the first movement of the Eroica. I don’t think I ever saw him so happy. From that moment he started to help me and became a wonderful teacher. He said I should have contact with other teachers and he supported my interest in repertoire other than his own—he was not at all like a guru. He developed my memory by getting me to conduct without a score.’