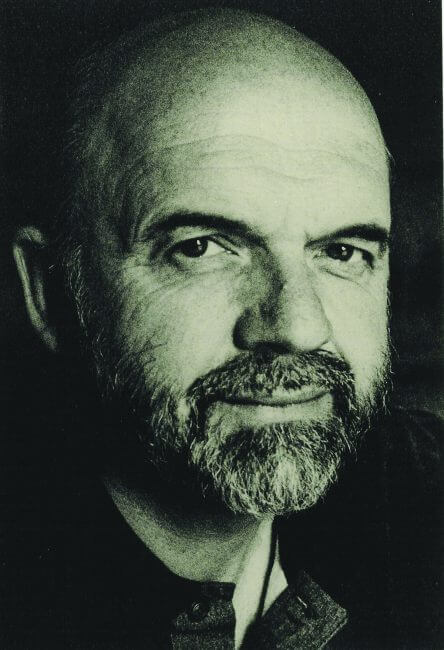

Robert Tear, 1939-2011

April 2011 in People

Anthony Holden

One of Britain’s best-loved tenors—also a conductor, teacher, author and raconteur—Robert Tear died on March 29 after a brief illness, aged 72. With a repertoire ranging from Dowland to Dove, he was, over the course of a long career, a huge presence in the musical world. The journalist Anthony Holden remembers a man whose friendship enriched his life.

In the late 1980s I moved with my growing family into a small west London square bordering on Ravenscourt Park. Exiting our front gate one day, I bumped (literally) into a figure whom I instantly recognized as one of my favourite musicians.

‘Good heavens,’ I exclaimed, ‘you’re Robert Tear!’

‘Hole in one!’ he replied. ‘And you must be our new neighbour.’

Bob turned out to live a minute’s walk away, directly across the square. And in no time at all he had become a firm friend, as warm and wise as he was (often) wacky. He would usually ring my doorbell as he made his morning excursion through the park to the local pub; I would tag along as he talked about everything and nothing with a combination of energy and candour. Sometimes we would carry on over lunch at the nearby gastropub.

Over many hours of intense, wide-ranging conversation, often at home with his beloved wife, Hilary, I came to know Bob as a supremely intelligent, well-read man with an unusually wide span of interests and enthusiasms, not slow to voice his opinion on matters great and small. Alongside his musical career he wrote (and published) poetry and prose, made and collected paintings, notably watercolours, explored Eastern and other philosophies, and held strong, sometimes acerbic, always witty views on whatever came up. His playful exterior could belie an essentially high seriousness of purpose.

I had long known his work, of course, as one of the most versatile and meticulous of British singers, at home in repertoire from ditties to high opera. With his friend Benjamin Luxon he had recorded Victorian parlour songs ripe for revival; with his friend Bernard Haitink he reached the heights of Wagnerian excellence as the Royal Opera’s Loge. Soon after our first meeting, I went with Hilary to see him as a flamboyant Ringmaster in The Bartered Bride, then at Sadler’s Wells during the closure of Covent Garden; and later as Basilio in Le nozze di Figaro, once the company had returned home. In 1993, when I published a fierce assault on the monarchy entitled The Tarnished Crown, the copy I carried across the square for Bob and Hilly was inscribed ‘Era solo un mio sospetto …’

Slowly but surely we acquired mutual friends as disparate as his manager and longstanding chum Martin Campbell-White of Askonas Holt, and the ‘roots’ singer and political activist Billy Bragg, who for some years enlivened our little square when he lived next door to the Tears. Another simpatico arrival in the square’s handful of houses was Robert Butler, then the drama critic of the Independent on Sunday, who was happy to be known as Bob Junior in the Holden family’s ‘Rave Square’ nomenclature.

Further afield, Bob Senior introduced me to Kiri Te Kanawa backstage in San

Francisco, while he was singing Herod, one of his favourite roles, to her Salome. In turn I introduced Bob to my dear friend Frank Kermode, the eminent literary critic, and a learned lover of music; in 1999, when I co-edited a volume of 80th-birthday tributes to Frank, Bob came up with some elegant quatrains self-adorned with festive laurels.

One Sunday in the mid-’90s Bob called to ask with humble apologies if I happened to be free that evening to drive him to and from the Festival Hall, where he was due to sing in Beethoven’s Choral Symphony. He had never himself learnt to drive, and Hilly, who drove him everywhere, was suddenly needed elsewhere. I sat with delight through a wonderful performance, during whose last movement Bob seemed to be looking straight at me from the stage as he lent especial force to the tenor’s climactic top B flat. ‘I felt like you were singing that thrilling note just for me,’ I told him as I drove us home. ‘I was!’ he replied with a wicked nudge that almost steered us off the road. ‘My way of saying thank you.’

I would love to have heard his Lensky (Royal Opera, 1970), whose pre-duel aria is a permanent fixture on my ever-changing list of Desert Island Discs. But perhaps Bob’s finest hour on stage, in my personal experience, was his Aschenbach in Glyndebourne’s 1992 revival of Britten’s Death in Venice. He was, unusually for these days, quite as fine an actor as singer.

Bob had, of course, made his name in Britten, despite somewhat turbulent relations with the ‘court’ at Aldeburgh, as chronicled in his idiosyncratic and very funny 1990 autobiography, Tear Here. (It was typical of Bob to insist on a sight gag on the self-illustrated book’s dust jacket—a diagonal dotted line for the reader to, yes, tear here.) These musings continued in Singer, Beware! (1995).

He had made his operatic debut in 1963 with the English Opera Group, as the Male Chorus in Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia, and soon had Britten writing roles for him (notably in two of the Church Parables). For all their fallings-out, Britten had ordained him the natural heir to his lifelong muse, Peter Pears. In Pears’s wake, Bob made such roles as Peter Quint and Peter Grimes distinctively his own. He much preferred Michael Tippett as a colleague, however, if not quite as a vocal composer; he pioneered the role of Dov in the The Knot Garden (1970) for Tippett.

Bob’s subsequent career took him all over the world, as a singer and later as a conductor, showing his versatility in works from Penderecki and Berio to Gordon Crosse, from Paris via Munich to New York and California, and making his conducting debut in Minneapolis. But he never lost touch with his Welsh roots. Born in Barry, Glamorgan, on 8 March 1939, Bob remained fiercely proud of his Welshness (and his Welsh bride of 50 years) as he progressed via a choral scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge (where he forged a close alliance with David Willcocks) to become a lay chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral. It was the beginning of a 50-year career spent, as he liked to put it, ‘singing for money’. His gift for engagement with people of all ages must also have made him a wonderful teacher, during his 25 years as the first Professor of International Singing at the Royal Academy.

In the early 2000s, when my second marriage had imploded and I was madly pursuing a potential third Mrs Holden, I inquired about her taste in music. She said she had always remembered a beautiful aria in Handel’s Semele, which she had heard sung in the mid ’80s by someone called Robert Tear. ‘Darling,’ I didn’t say, while knowing it was true, ‘I can get him to sing it for you this evening.’ But I did consult Bob for details of a recording, dramatically had it FedExed over from the States, and got it transferred onto CD in time for my next romantic meal with her. Maybe, I suggested to Bob, he should bring it into the restaurant himself? ‘I don’t think so, my dear,’ he replied sagely. ‘This is all getting rather too Milk Tray.’

When I unexpectedly became a music critic for The Observer in 2002, Bob’s merciless teasing was always leavened by absurdly generous praise. But it did not get in the way of our friendship, even when we disagreed. After I had written warmly about him several times, he repaid the compliment in 2005, when I published a life of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist, which he reviewed with equal warmth for The Oldie. In 2004 I reviewed his 65th-birthday recital at the Wigmore Hall, which showcased his love of poetry as much as his unparalleled vocal range, from Britten’s Holy Sonnets of John Donne via Madeleine Dring’s Five John Betjeman Songs to Jonathan Dove’s setting of Bob’s own poems, Out of Winter, a knowing riposte to Britten’s settings of Hardy, Winter Words. ‘The best birthday present he has given himself, and his loyal following,’ my piece concluded, ‘is a firm refusal to retire.’

Later I heard him at the same venue in a new role, as narrator of Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale; recently he read extracts from Mozart’s letters to a musical accom-paniment at Kings Place. Bob continued to conduct and sing until 2009 when he turned 70, making a final appearance at Covent Garden as the Emperor Altoum in Turandot. In the ensuing 18 months, he had been relishing his retirement, surrounded by his family, with another burst of intense reading and writing, until the cruel onset of cancer.

In a twelvemonth that has also seen the deaths of Philip Langridge and Anthony Rolfe Johnson, this has indeed been a grim season for Britain’s own outstanding Three Tenors. For my money, Robert Tear was always primus inter pares, not just as the man with whom I was lucky—and privileged—to forge a friendship that enriched my life. His 250-plus recordings will keep his wonderful voice poignantly with us forever. But for me and countless others, his is a tragically premature loss. He will always retain a special resonance, as singer, satirist, sage and much-loved friend.