The Handmaid’s Tale

English National Opera at the London Coliseum, April 10

On April 7, on the eve of the opening night of The Handmaid’s Tale, a young woman in Starr County, Texas, was arrested and charged with murder after she ‘intentionally and knowingly caused the death of an individual by self-induced abortion’. Proof, if proof were still needed, that Margaret Atwood’s classic 1985 novel was never a dystopian flight of fancy but rather a warning, rooted in history, that democracy is fragile and that totalitarianism lurks just around the corner. Recent events, from the renewed subjugation of women and girls in Afghanistan by the Taliban, to the use of rape as a weapon of war by Putin’s troops in Ukraine, have served only to reinforce the ongoing relevance of Atwood’s work. It is never not timely.

So it is a powerful statement by ENO’s artistic director Annilese Miskimmon to choose to make her company directorial debut, not with a Carmen or a Butterfly, but with a new production of composer Poul Ruders and librettist Paul Bentley’s operatic take on Atwood’s novel. Powerful because, as she comments, the opera ‘reflects the reality of many [women’s] lives across the world today’. Powerful, too, because, in the context of a work that ‘puts a woman and the experience of women at its heart’, Miskimmon has brought together an all-female creative team—a direct challenge, one might say, to a professional operatic world that still discriminates against women (see my ‘Firing the canon’, opera, February 2021) and that has hardly even begun to address the questions raised by the #MeToo movement.

If Atwood’s novel achieves its disturbing effect by means of the objective way the narrator Offred describes the horrific situation in which she finds herself, the opera through its music brings a new depth to the representation of her feelings and emotions. Highly varied orchestral writing underpins the twists and turns of the plot, from moments of extreme melodic simplicity to an overwhelming barrage of dissonant brass and percussion. Sustained lines capture the desolation Offred feels; distorted echoes of ‘Amazing Grace’ rise from the pit to comment on the perverse morality of the monthly ritual impregnation; swirling strings envelop Offred as the Commander forces his first illicit kiss on her. Indeed, Offred becomes a kind of latter-day Wozzeck, as it is only through the eyes and ears of this central abused character that we can encounter the Republic of Gilead. Kate Lindsey’s playing of the role is, quite simply, faultless. On stage virtually throughout, she completely inhabits this nightmare existence, maintaining an extraordinary intensity through her clear and finely controlled singing. The stillness of the lines in which she intones her feeling of emptiness, shutting down all vibrato, is as shattering as her expressionist screams of agony as she relives, over and over, the abduction of her daughter. The tenderness of her brief time with Nick is striking in a work where any kind of affection is, for the most part, absent. Astonishing is the moment where Offred duets with (a recording of) her past self, poignantly capturing a sense of being trapped between worlds.

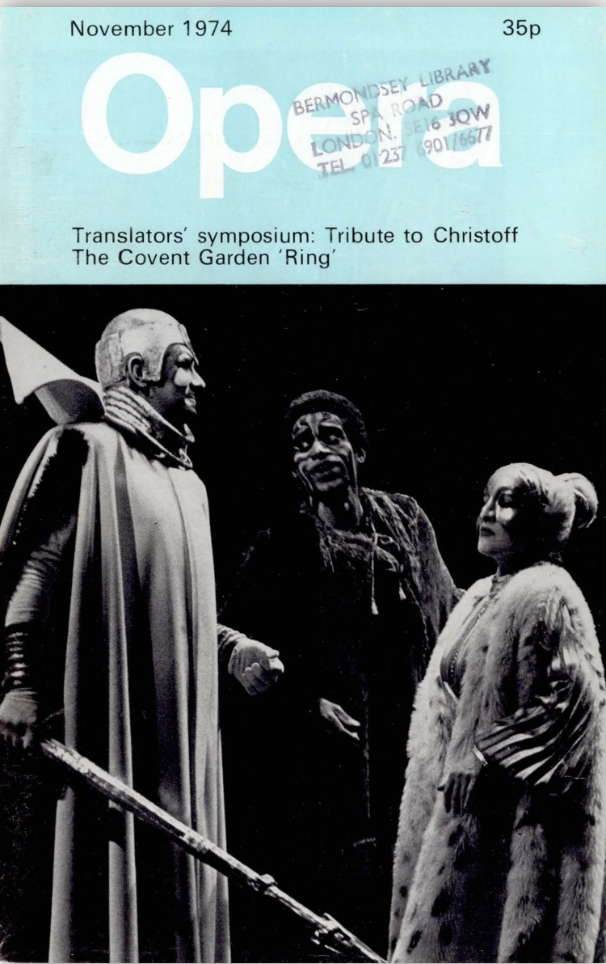

Equally strong performances are given by the richly coloured contralto Avery Amereau as Serena Joy, bitter and spiteful to the same degree as her husband the Commander (Robert Hayward) is creepy. Pumeza Matshikiza as Moira has a beautiful voice, powerful, punchy, making the best of the sometimes ungrateful lines given her by Ruders. Emma Bell is terrifying as Aunt Lydia, delivering music of extreme virtuosity that perfectly depicts the overzealous certainty of this true believer of the Gilead doctrines. In other roles, Rhian Lois (Janine/Ofwarren), Frederick Ballentine (Nick) and John Findon (Luke) all make fine contributions.

Annemarie Woods’s designs and Miskimmon’s direction espouse an effective simplicity, save for the seemingly ancient, colossal Wall to which photos of hanged rebels are affixed. Much is achieved with lighting (by Paule Constable) and curtains. The Time Before is invoked by black-and-white video projections (by Akhila Krishnan) to interrupt periodically the flow of the narrative. The crowd scenes of massed handmaids chanting in rhythmic unison are particularly chilling, articulating simultaneously the women’s forced obedience and pent-up rage. And all this is supported and coloured by some outstanding orchestral playing, conducted by Joana Carneiro, who judges well the ebb and flow of the music, the lyrical as well as the monumental. If there are times, especially in Act 2, when things seem to drag a little, then the fault lies not with the production but with the librettist’s desire to be faithful to every major episode from the Atwood novel. And while in the book the epilogue set in the year 2195 is a brilliant literary coup, to make this academic conference the frame for the opera serves only to weaken the impact of the drama which, as I say above, prioritizes feelings over events. The ending of the opera, as of the novel, is uncertain. What happens to Offred is unknown. Is she ‘sent to the colonies’ by the all-seeing secret police? Or does she escape, abetted by the underground movement? Miskimmon gives the character agency, really for the first time in the opera, as she is seen running through mist and clambering over the Wall. It is a striking closing image that offers a tiny ray of hope that this republic, like so many repressive empires before it, can be resisted, that it will fall. For all its representation of violence, for all its portrayal of sickening forms of suppression, this outstanding production from an excellent team is nonetheless testimony to the possibility of a changed world in which women can and will find the means to regain control of their bodies and lives. Jonathan Cross